Interview

Rob Hudson

Rob Hudson describes himself as a ’conceptual landscape photographer’ and lives and works in Cardiff, Wales. His work, which is always in series, explores how we relate to the landscape.

Chris Tancock is perhaps best know in the landscape photography world for his colour Quiet Storm series for which he was highly commended in the very first Landscape Photographer of the Year competition in 2007. There is a double irony here, firstly because at least 99% of his work is black and white and secondly because he denies being a “landscape photographer” at all, preferring to label himself as a “rural documentary photographer”. But don’t be put off that this is not relevant to you as a landscape photographer, trust me there are some huge lessons to be learned from this man and his application of method and technique and although he pursues his own angle the work still deals with the things we can all find in the landscape around us. His work is poetic, magical and original and maybe shows a route to furthering the depth and meaning in all our work and surely that’s a conundrum we all face from time to time. You may, though, have to stomach some blunt and candid criticism of the landscape genre from him before you see a route to the creative future, for it’s only through criticism that we can move forward.

Chris Tancock is perhaps best know in the landscape photography world for his colour Quiet Storm series for which he was highly commended in the very first Landscape Photographer of the Year competition in 2007. There is a double irony here, firstly because at least 99% of his work is black and white and secondly because he denies being a “landscape photographer” at all, preferring to label himself as a “rural documentary photographer”. But don’t be put off that this is not relevant to you as a landscape photographer, trust me there are some huge lessons to be learned from this man and his application of method and technique and although he pursues his own angle the work still deals with the things we can all find in the landscape around us. His work is poetic, magical and original and maybe shows a route to furthering the depth and meaning in all our work and surely that’s a conundrum we all face from time to time. You may, though, have to stomach some blunt and candid criticism of the landscape genre from him before you see a route to the creative future, for it’s only through criticism that we can move forward.

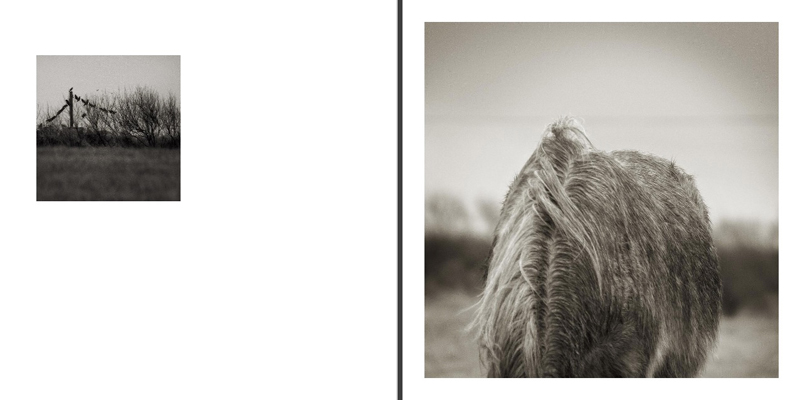

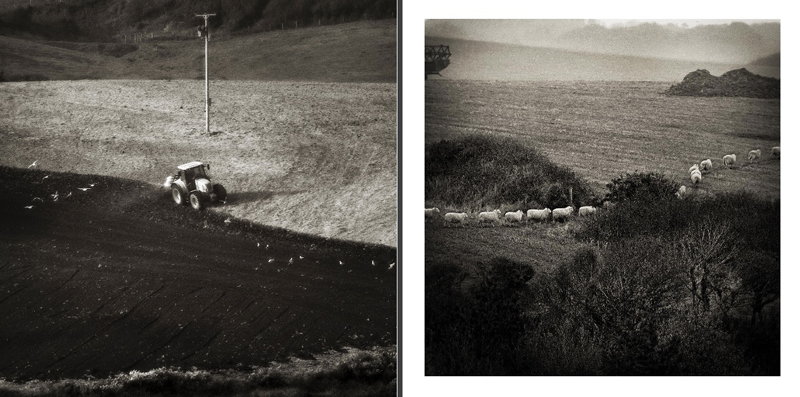

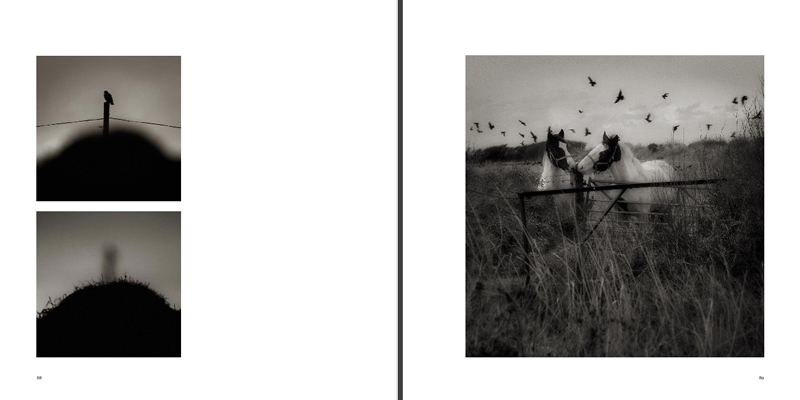

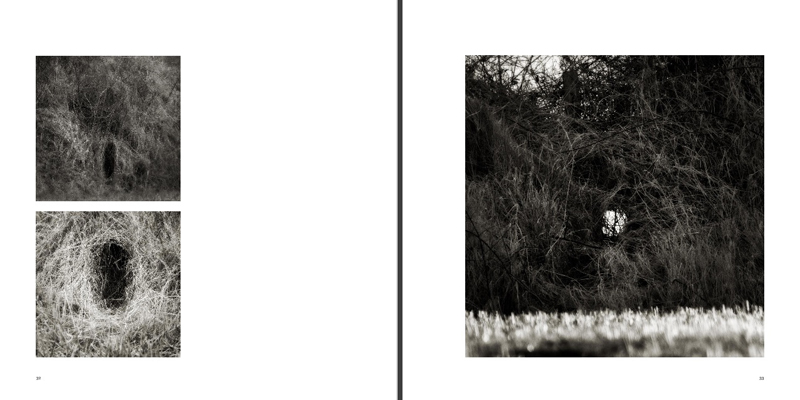

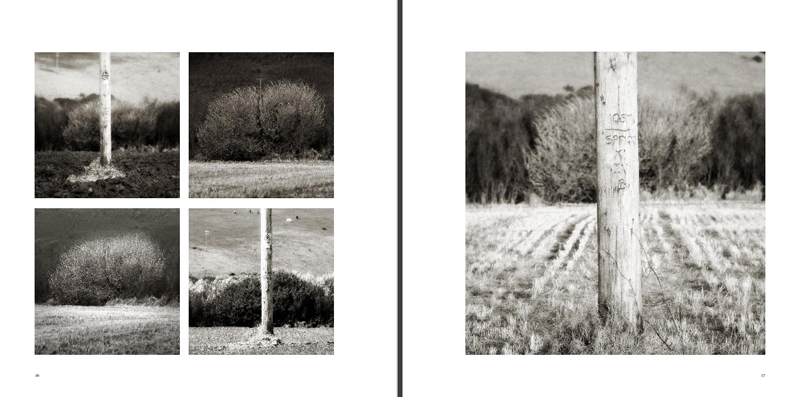

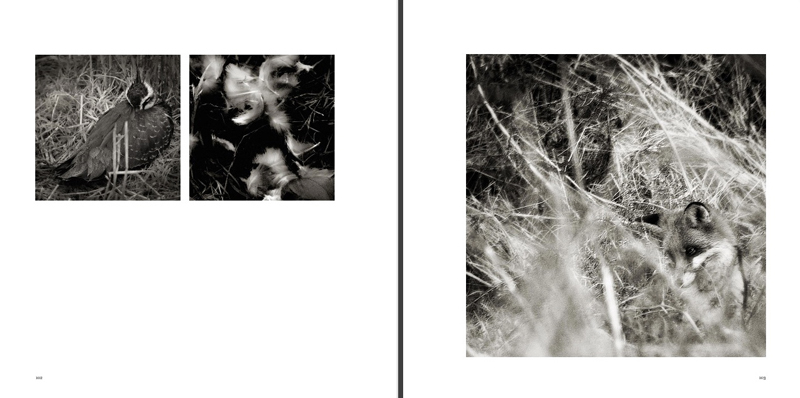

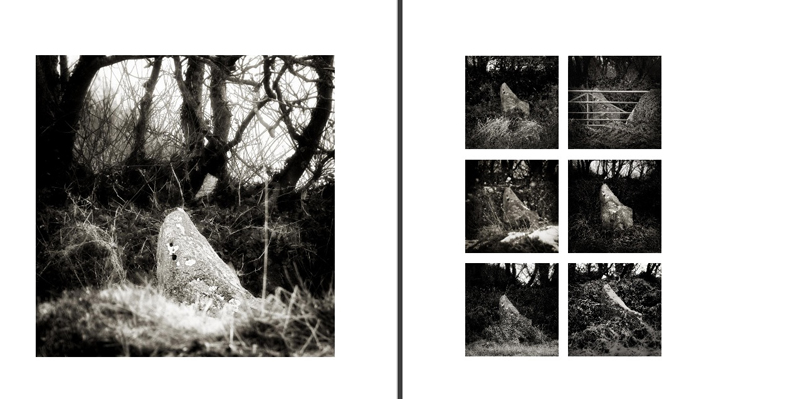

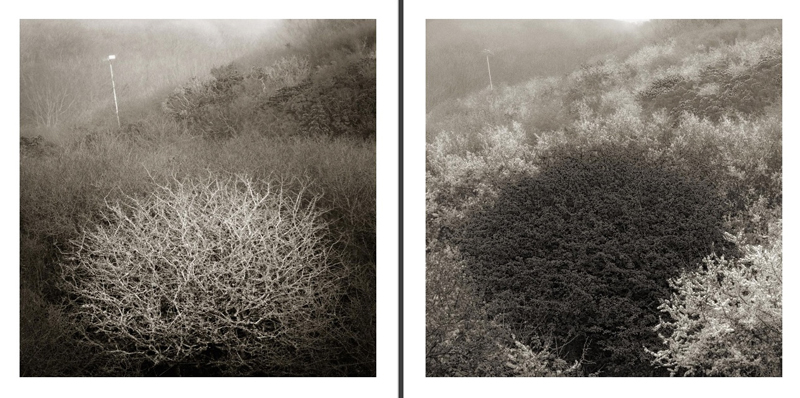

The Quiet Storm project represent only 12 images, although apparently ongoing he hasn’t added to them for nearly two years. He should perhaps be better known for his other work, all of which is black and white; Wildwood which explores the way we see images through the exploration of animal like forms in ancient woodland, the Stones series which examines the relationship between man and his environment in closely framed images of stones and the changes wrought be nature over time and finally and perhaps most importantly the major project Beating the Bounds that has been three years in the making and has another year or two to completion. Simply subtitled “five fields, five years” it is a substantial body of work already and to my mind the most successful to date. In essence it is a journey through time in five fields that are completely unremarkable to the casual visitor and certainly your average landscape photographer would dismiss them without a second thought. But that was a deliberate choice, one that has forced him to confront the norms of composition and subject and to weave together a series of images that represent the remarkable things that happen in such unremarkable fields, the passage of time and in the end his relationship with his chosen plot as it evolves throughout the project.

As we sat chatting in his kitchen, the table between us soon became strewn with his beautifully crafted prints and books representing his influences such as Fay Godwin’s Forbidden Land and most often referred to was John Berger and Jan Mohr’s Another Way of Telling. Other names that cropped up included people such as Josef Koudelka, the poets John Clare and Alice Oswald, the magic realist author Angela Carter, the naturalist Richard Maybe and the photographers Keith Carter and John Blakemore. They not only represented the breadth of his insight, but also his infectious passion for photography as he continually drew out complex ideas and strands while referring to them. I found the ideas inspirational and, as if I needed more, I was constantly reminded of the power and poetry of his work by the liberally displayed prints scattered around the walls of the room.

What do you think of the Landscape Photographer of the Year Competition? (Chris Tancock was highly commended in the very first one in 2007)

“Um, it’s a very good commercial enterprise and that’s all I feel about it really. I mean it’s great for the people who run it and the amateurs who enter it but it shouldn’t be called the Landscape Photographer of the Year. The thing about photography is that you can accidentally take a brilliant image. I often look at the winners website and they have one good image and I look at the rest and they’re not as outstanding as the winning shot, a lot of them are just copies of other photographers and in exactly the same location. In America in the 30s when Kodak was really trying to push itself, all the beauty spots in America they had these plinths with footprints on them and it was a Kodak plinth, you stood on them, pointed your camera in the direction of the arrow and you had the “perfect shot”.”

“I keep waiting for there to be another brilliant landscape photographer, somebody like Fay Godwin or Bill Brandt or even Koudelka - his landscapes in Wales especially. Or Raymond Moore he influenced so many landscape photographers. Fay Godwin went on one [of his courses] when she was doing a cross over from portraiture. His work now looks old hat, because it’s what you see all the time, but for it’s time, you can see there’s a Koudelka feel to some or a Michael Kenna feel to this [pointing out images on his laptop], but this was done way before any of that, photographing things in the landscape that most amateurs would ignore. I’m always getting told off for leaving telegraph poles in, but they are there and they are wonderful and they wont be there much longer.”

“I don’t want to hurt people’s feelings, but I don’t like boulders in the foreground, sunsets in the background, diagonals in between them, repeated again and again and again, hunting the countryside until you find these things. What does that tell you about the landscape? Nothing, it tells you about composition and the photographer, it doesn’t tell you anything about the landscape, but they’re commercially viable. They are very easily read images. People forget we read images on different levels and an image like that has the reading age of a 5 year old, it’s the equivalent of a Janet and John book. If you call it the Landscape Photo of the Year I wouldn’t have any problems with it, but to call it landscape photographer makes it sound like this photographer has done amazing things with landscape, but they’ve taken one good shot - it could have happened by accident. They might have one good photograph, they might have half a dozen, but that doesn’t make you a good photographer, especially if you have a digital camera. To me that’s the main difference between different sorts of photographers and what I call calligraphy photographers, which is definitely, what the LPY is about. It’s about good composition; it’s about crispness, all these things, that is calligraphy. What is that person telling me about landscape? What is he telling me that he feels about it? Forget the composition, forget the detail, what else is there and I look at those and I don’t see anything else.”

So how did it affect you, being commended?

“Well it was the first year, I didn’t know what it was going to be about, I didn’t know what sort of people were going to enter. You know, the idea excited me a bit because even though I’m not a landscape photographer I thought there isn’t anything out there being done. I consider myself a rural photographer and I consider myself a documentary photographer who falls into fine art, I love the idea of mixing documentary and fine art together.”

“I was quite excited to start with, there are some lovely landscape photographers out there, nothing amazing, nothing that’s making me go “oh my god ,I wish I could do that!” But there are some interesting people out there, they didn’t enter and that’s why I haven’t entered again, it’s not what I do. When I went to the winners exhibition my work was scattered about (which is understandable) I talked to people about how I’m using set locations and I use the same locations again and again and again, and I’ve only got 12 places I go to [for his colour Quiet Storm series] and it’s about photographing storms, it’s not about the landscape. If I lived in the city they would be cityscapes. The storms tend to happen on the beaches because there’s big open sky to show the storm. I did shoot myself in the foot in a way and that project has been a big learning curve for me. I decided in the beginning to choose a dozen locations so that hopefully I get multiple storms in the same place making the landscape look different, I also wanted to use really simple compositions, thinking that if the composition was really simple people wouldn’t focus on the landscape and it didn’t work, it backfired.”

Do you think you’re now known for those colour images?

“Well I am, I’ve got 12 colour photographs and the rest is all B&W, more than 98% over 30 years of photography is B&W. I don’t see the point of colour. Just because a photograph can do colour, can do 3D, can do movement, it doesn’t mean we have to use it. For me to do a 3D image there would have to be a really good reason for that, for me to do a motion picture there would have to be a really good reason, for me to do colour there has to be something really important about it to my story.”

“Well I am, I’ve got 12 colour photographs and the rest is all B&W, more than 98% over 30 years of photography is B&W. I don’t see the point of colour. Just because a photograph can do colour, can do 3D, can do movement, it doesn’t mean we have to use it. For me to do a 3D image there would have to be a really good reason for that, for me to do a motion picture there would have to be a really good reason, for me to do colour there has to be something really important about it to my story.”

“The idea with the storms was that I’d seen two or three storms in the middle of the day, that looked like sunsets, and I thought wow this is amazing! So I started to photograph storms, where through exactly the same reason as sunsets, filtering out light, created these really weird colours, so it had to be colour. I didn’t want other aspects entering into it, so that’s why I chose to use exactly the same camera, exactly the same location and exactly the same simple composition each time, I was trying to eliminate everything else. It didn’t work out quite the way I wanted, but then things don’t always work, you know I wish they did!”

“The biggest thing to remember about photography is to remember a photograph, never, ever, ever, ever shows you reality. It’s one of the reasons I’m not keen on landscape photography (this is going to sound terrible, but I’m not) is that people think they are showing reality, or they are trying to. They want it sharp and they want the tonal range to be like the eye sees, I can’t be bothered with that. I talk to so many [landscape photographers] and they say that is how the eye sees and I say yes, but the eye sees movement, they say photography doesn’t show movement and I say yes it does. What’s film? One still after another still after another showing you the illusion of movement, photography is an illusion.” CT reaches for a print, pointing and continues: “This doesn’t exist. What are we looking at here? A piece of paper with ink on it, can you see the piece of paper with ink or can you see the picture? It’s an illusion, your brain does not look at the ink, it reads all these lines, tones, shapes and your brain recreates them into an image in your head, it doesn’t exist. It feels like they’ve forgotten what photography is. Photography is showing the world as a photograph, not showing the world as it is, it’s saying wow, I wonder what the world looks like as a photograph.”

“They seem to ignore 90% of what photography is and keep hold of that 10%, they focus on detail, on depth of field, tonal range and they think that’s the most important thing. When they want the colour to be exact they have these profiles, what’s wrong with your eyes? When I was in the darkroom, I’d produce test prints, and look at them and I’d say yes that’s good and I’d do it!”

“Photography for me (I’m quite old fashioned about this I suppose) is about juxtaposition, it’s about telling stories through images, it’s a documentary idea, the old fashioned idea of documentary, the John Berger idea, you selectively show people, it is about a body of work. I cannot for the life of me get excited about most individual images, because an individual image can tell you very little unless it’s extraordinarily good. Some of the best Cartier-Bresson can go beyond that, but they’re one in a million, or a great Atjet. There are people out there who’ve achieved those individual images. What most landscape photographers do I would call calligraphy, they produce pretty pictures and they use standardised techniques, so you have the thirds system with foreground interest and a strong diagonal and they hunt the countryside to find images that conform to some compositional ideal so they keep moving on until they find somewhere else that fits. For me that’s where it all falls down, you end up with these random images and nobody bothers, on the whole, reading the image. It’s a bit like having a poem written in calligraphy, you stand there and go wow. The funny thing is that this calligraphy has very little to do with the photographer, the calligraphy is also the technical side of photography, number of mega pix, quality of the printer etc. Composition is a bit like spelling, it’s no big deal. We all have to learn to write so that others can understand what we’re saying. It’s exactly the same in photography, we shouldn’t be praised over it, we don’t praise writers because they get their spellings right, so why do we praise photographers for doing good composition? I don’t understand it, it’s bizarre, it’s just a basic but important starting point.”

Is your choice of camera important to you?

“Think of a photographer like a carpenter. If I gave a carpenter a chisel, what could he make for me? Give him a saw and a chisel and a plane he starts to make something interesting. I’ve lost count of my cameras; I’ve got a large format, a little Leica, medium format, a pin-hole camera. At the moment on Beating the Bounds, I’ve got two or three of these little Olympus’ [DSLR]. I like them because they take all my Leica lenses, whereas for the Quiet Storm project, I’m using an old Minolta 4.5mp because I don’t want detail. For the new farm project, I’m using a 12mp camera. I’ve got my film cameras and I’ve got a large format. They all give you different looks, they are all different tools. You choose your tool for your job. The idea of having one camera, I don’t understand it! Cameras don’t cost a lot anymore [second-hand], the crazy thing about buying the latest Canon or what ever is they’re gonna have to replace it a year down the road because they’ve got to have the latest mega pixels or the latest features. I hate features on cameras, oh god I hate them! I take all my photographs on manual. I was going to say, I use manual focus but my eyesight is not what it was. So what I do is set up the camera on auto focus and then go to manual [to take the photograph]. I use the spot focus - that’s another thing, why would anyone want to let the camera focus on anything it bloomin’ well likes! Matrix focussing, what is that about? It’s the same with the amount of light coming into the camera; I want to choose how much light comes into the camera because I want to show the world as I want it to look. That’s what photography is about. A camera doesn’t understand what you’re looking at, it doesn’t know anything about what you want to say and how you want to say it, it takes averages. I hate averages! Focus, exposure and depth of field, they are the three basic things within photography and people don’t want to be involved with them. They are what make your photographs yours, rather than the cameras. It’s the same reason I don’t like a lot of landscape photography because you can see the camera’s taken the photograph for them.”

Tell me about post processing, how has that changed over time?

“I photograph in RAW (at least in digital), with a film camera I have to make decisions; I have to decide what a photograph is going to look like. So if I wanted a warm tone image, I bought Kodak, if I wanted a cold Germanic image, I bought Agfa, if I wanted punchy bright coloured images I bought Fuji. They all had different dye saturations, different contrasts even; you choose your film to get your look. These days a RAW file collects so much information it’s possible for me to have a little add on and as soon as the RAW file comes into Lightroom it gets converted to look like Fuji. So it means all your images are going to be standardised as they were when you bought film. Then I dodge and burn, for me (this is really personal) a photograph that hasn’t been dodged and burned is a snapshot. I dodge and burn mainly to control how I want people to look at my photograph and to give a sense of depth and mystery and all the things that bring an image to life. Then when it came to printing in the past, you had a choice of papers to give you the look you wanted. Your developers would give you different tones, all these things would give you completely different looks. I was a Record Rapid man. Same with colour, the paper I loved, even though it was really expensive, was Cibachrome. So I’ve got my printer set up to put down exactly the same colour saturation as a Cibachrome print. All my colour images are printed exactly the same, so any changes in the colours are to do with the reality of a moment in time.”

He uses post processing to dodge and burn and give them the tonal range that would have been achieved with “Record Rapid” paper, “Because I haven’t got that option anymore, I have to do it myself, rather than have some chemical manufacturer do it for me. That is the great thing about digital photography - in the past I would dream of a film or a paper and unless I’d been a billionaire I couldn’t have achieved it. Digital photography is not cheating, that’s what photography has always done. A photograph is a chemical or now a digital process that alters the world from what it is into a photograph and to think of it as anything else is silly, really silly - I can’t emphasize that enough - it’s not a window onto the world, it’s just not.”

“So I’m processing my images to give them tone, I’m setting the contrast to get the contrast I would have got with the paper, if it’s a digital shot I even put some grain back into it. I love grain and I hate the fact that a digital camera doesn’t give you grain. Noise isn’t the same, because grain clumps and works in a completely different way.”

“I do everything by eye, so I drag out some old Cibachrome prints and the original slide and put it in the computer and play with it until the look is as close as possible. John Blakemore, darkroom wise, was my guru. I still use the techniques I learnt in the darkroom. Now, I like to use Photoshop sparingly as if I was back in the dark room but what I do love using it for is my initial test strips and for dodging and burning. They could do with somebody like John Blakemore or some old time darkroom photographer to say, “If you had this in Lightroom...” it’d be great. Although Lightroom now has ‘dodge and burn’ it feels nothing like working in the old darkrooom, which is a shame. Whereas in Photoshop I’m more able to work as I did in the past. I would, for example, work with templates cut to shape.”

“It’s a funny one because I love digital and film but with digital I can work on a five year project like Beating the Bounds and I can just get on with it, I haven’t got this mound of negatives. So it’s a bit like a writer who says I don’t need to use an old typewriter anymore, I can use a word processor, it doesn’t change what he writes, it’s just a tool. There are for sure limitations, but some of these shots in Beating the Bounds are digital, some are film. Digital photography is going to supplant film, the same way wet collodion isn’t about anymore.”

“On my Wildwood project it’s not about the wood, it’s about how we look at images. It’s about photo’s being nothing more than photo’s We read an image and the thing is we make mistakes. What I was photographing in this image was a wolf”. [Looking at the image Wolf Study see below] “And when I put it out on display some people said, “it’s not a wolf, it’s a deer” and others, “I see a sheep with it’s wool falling off” others “I see a tarantula” and for the life of me I can’t see a tarantula. I had a young lad come who said, “I see your wolf, but I see a big ear and a nose and an eye and I see a rabbit.” It just went on and on people seeing more and more things, so this project is about how we see things. On a superficial level it’s the wood, I love the ambiguity of images, this project is about reading images and reading into them. It’s a slow project, I have to find all the things, most of my projects are slow. I work like Keith Carter does, I have my boxes and I just keep adding to them it can take years, but what’s the hurry. It’s about understanding, exploring photography, exploring the way you communicate, it’s not about wanting to produce pretty pictures that people will say “Oh that’s nice”.”

“ I have none of the shots that I took from the first year of “Beating the Bounds” because that year was about getting to know what I wanted out of the project. I didn’t know how or what I was going to photograph in those fields. I have an idea, like the idea of Beating the Bounds about walking the same route, about photographing things that aren’t clichéd, beautiful things that other people may not look at. Hedges! I always wanted to photograph hedges but how do you photograph hedges? Most people don’t even look at a hedge; don’t even look at fields but as I walked those fields I got more ideas about looking over boundaries, to do with separation, with focusing on what’s yours and what’s not. It’s also about the way a field looks as though nothing happens in it. After walking it for a year it really came home to me that the great thing about a field, unlike photographing in a city – photographing on the street is like photographing a second-hand on a clock, there’s something happening all the time, photographing a field is like photographing the hour-hand, you know it’s changing but you can’t see it happening. You may have to wait weeks, months, years before something happens. Now I can walk up the field and photograph nothing because nothing happened, but you may go up on one day and a lot is happening. Maybe there’ll be a change in the seasons and suddenly a lot happens.”

“What I love as well is things you’ve looked at before a hundred times, that never caught your eye, will suddenly become really important and things you’ve been photographing for three years suddenly die away and you don’t want to photograph them anymore. I love that idea of photographing over very long periods in one place. All my projects have been long periods, the shortest one I’ve done was a year and I felt that was too short and I don’t think I’d do one for just a year again, it’s not long enough! Five years is a good time, three years is the average, but of course you’ve got to have some work under your belt if you’re waiting for five years for a body of work.”

“It’s important to mention that the things I say about photography, what I believe, I really don’t expect other photographers to buy into it, I hope they don’t because that would be boring! Finding your own way is the important thing.”

Tancock has some fascinating ideas about how his images should be seen, or displayed.

“I think all pure photographers should be pushing the boundaries, photography is going through a very stale period at the moment. It probably did every time there was a technological jump, like when we went from wet collodian to dry collodian or from plate to film. The impact of the technology just made everyone brain dead, so they weren’t looking to do new things, then suddenly once they got used to it and it wasn’t new anymore then they thought “Oh my god, what can we do with this?” How different is it to use a Leica from a plate camera? So I’ve got a digital camera, how is that different to when I was using 35mm and film? Doing this project [Beating the Bounds] is one of the experiments.”

“The idea is to have a project that will have four to five hundred images at the end of the day. To be read, in the form of sentences. images feeding off each other in a structured way, size is one way I am trying.

People think that an image can be any size, that it will make no difference, the main reason for it is a large image is powerful, a large image has impact, it’s just the nature of the beast. Any image blown up large is amazing!”

“My ideal way of seeing images is in a book, you sit down on your own and you look at it, you experience it. The largest I’ll go in an exhibition is 40x40cm, it’s a two person experience, I’m happy with that, just about. I’d much prefer they were smaller, but people want big images and the biggest problem with my work is that I don’t see my work as individual images; I don’t want somebody to walk to that image and look at it individually, because it is part of a body of work. It’s like approaching a piece of literature and only bothering with one sentence. So many people seem to have got it stuck in their heads that a photograph has to be like a painting, it has to be an individual image that can be appreciated like a painting, now personally I don’t believe that can happen; a painting and a photograph are nothing alike.”

l have to hint I think, give them a certain amount of help; I don’t want to have text. Text and photography has its problems, it can work, but if it’s just a description of the image you’re looking at then it’s pointless. People still want to look at my photo’s as individual images, until I get it in a book or a plasma screen and I’m controlling how people look at it. In my last exhibition I was watching people they were going to one image and across to another one, looking at the big images and ignoring the smaller ones. They think it’s a big image so that must be important. It wasn’t working, I learnt a lot from that exhibition, what I expected people to do they didn’t. I need to learn how to help people.”

How important is a sense of place in your work?

"It works in reverse, it isn’t important until I start photographing something then it is very important. [In Beating the Bounds] I chose the fields at random, the place wasn’t important. The project was initiated by ideas, ideas of retracing steps, photographing from set points, photographing something other people don’t look at. People come on holiday to Pembrokeshire and they stand and look at the sea, with their back to the fields. Fields are really amazing nature reserves. The farmer maybe goes into the fields four times a year and he rarely ever gets out of his tractor. In the nature reserve where I photograph the trees that look like things, I see far more people than I do in the fields! Basically I don’t meet anybody in the fields.”

“I can’t think of anything where I’ve thought, “oh I must photograph there”, it doesn’t start like that, it starts with an idea like “I want to photograph life on a farm”. How do I want to photograph it? It’s only once I am really well into a project that the sense of place seeps into my work. I’m looking for new ways of doing documentary photography, so I’m incorporating things like fine art into documentary; I’m incorporating things like wildlife photography into documentary. I really feel photography needs a shake up; it needs to be thinking of doing new things, otherwise we all go out and do the same photographs again and again and again.”

Is part of art personal expression?

“It is! Documentary is. There’s no documentary photographer that’s very been out there that’s ever photographed objectively. It’s all subjective, we choose what to photograph, what not to photograph. That’s what photography is, when you look at a photograph you are looking at the tiny, tiny amount of time and place that the photographer chose to show you. We leave out most of everything, most of the world, most of the time, it’s completely subjective and it lies. I love the fact that it lies, that’s the power of a photograph and everybody believes it tells the truth. It’s all an illusion. Like I said before a photograph is a piece of paper with ink on it and everything else is read and people read things differently. It’s all about what’s not shown, as much as anything.”

“I’m using very, very passive compositions [in BTB and Quiet Storm]. In other words I’m not cutting my subjects in half, I’m not having them in and out of the frame. Everything is within the frame, the trees aren’t cut off, unlike street photography where you get in very close and say an arm leaves the frame, that’s active composition. Passive framing is like Michael Kenna where everything is very pure, not cut off, suspended in the image, very passive. Cartier-Bresson’ s photographs are very active; he was always cutting people off, severing the tops of their heads and their arms. That is a subjective way of looking at things. People underestimate photography; it’s very, very complex. There are so many things you can do to make a photograph have a different effect on people. People who use “template” photography don’t understand that. They need to look at artists, one of the best artists to look at, as a photographer was Degas, he was one of the first artists to actually crop people. It hadn’t been done in art before, if there were people in the painting, they were all in the painting. So photography is totally subjective in the way you crop and reduce the world to a tiny element. Like Cartier-Bresson’ s Decisive Moment, it’s impossible to pick up a camera and not be subjective. The amount of people that come to me and say “did it really look like that?” It’s a crazy thing to say about photography. Because of course the world is not flat, the world’s not frozen in time, the world is not blurred, it’s not cropped, I mean what are you talking about!”

What are the limitations you’ve placed on yourself for Beating the Bounds and why? “The basic limitations I’ve placed on myself are the same limitations that most artists apply to themselves. The constraints actually help, without constraints it’s all over the place. I’ve always needed constraints because the more constraints I’ve got the better my photographs become and that works for any photographer I believe. So by physically creating restraints – by not leaving the track I can’t think, “oh if I was over there I’d get a better shot” therefore I can’t just do this or that. I have to start thinking “I am walking down this track. How can I tell my story?”

But is it forcing yourself to see afresh, is that the point of the restraint?

“Afresh yes, but also to look at the things again and again to try to find the magic in them. So I’m not thinking, “I’ll find something magical to photograph” which is what so many photographers do. I get so many people on workshops who say, “Where should I go to photograph? Should I go to Tibet? Should I go to Peru?” Why? What do you know about Peru or Tibet? Let somebody who lives there photograph it; there are enough photographers all over the world for that. If you’re a landscape photographer you think I must go to Iceland or I must go to Glen Coe. If you’re a documentary photographer you think I must photograph drug addicts or whatever.”

Is there an element of contradiction in you denying there’s a sense of place until you photograph it? “No, that’s not the same. I still start with an idea, I never start with ‘I want to photograph there’. There are a lot of reasons why I photograph around myself and one of them is because I believe people should photograph what they know about. I also believe why go anywhere else. If somebody from Tibet comes to Nolton Haven it’ll be the most exotic place in the world to them because it’s different, that’s all it is but what do you love about Nolton Haven? What would I know about Tibet if I went there? What could you photograph? Just the exotic. You’ll end up with National Geographic type photographs. I don’t like that genre, they don’t tell you anything, they are just pretty pictures, they are really so superficial.”

“I want to think, “what’s interesting about the things that I love?” So hedges, the countryside, farms (because I was brought up on a farm), basically rural life. That’s what I know about so that’s what I want to photograph.”

What’s the route of placing these barriers in place? What forced you into that?

“I just found the more barriers I have, the more restrictions I have, the better photographs I’ll take.” But what actually took you to that idea? “Commercial work, if you’re doing say interiors, you’re working to somebody else’s criteria, they come up with the idea. For a magazine the look has to be the look that the company needs. I can’t make them all dark and broody! So I have all those criteria that I had to work within and I found that helped me take good photographs. Artists have always worked like that. Magritte didn’t one day paint a Turner, one day a Constable, he had an idea and he set constraints on himself. Turner would choose a particular palette; he worked within that palette, he didn’t think, “I can have any colour I like”. Artists, writers and musicians have always worked within constraints, some more than others. Why don’t more photographers?”

“Once you’ve got constraints you can then focus on what you want to say. Then you don’t have to worry about all these other ideas. You can really focus on what you want to say and how you can communicate that to the person who is looking at it. They may not work, people may not get what you are trying to say, that’s not their fault it’s my fault. I then have to work harder to find other ways of doing it?”

“I know with BTBs I’ve gone quite extreme. Initially, I sat down and wrote out a list of the things I’m interested in, just randomly. I wrote down things like “folk tradition”, I’m fascinated by folklore; “ artefacts”, rural artefacts and the “visual history of the landscape”. So you could see where there’s a mark, you get hints of a hedge or a ditch, so you can start unravelling the past. The “memories tied up in somewhere”, I’m interested in that. The “wildlife in the landscape”, you know I never understand when I looked at all these landscape photographs, where are all the animals, where’s the wildlife? I’m interested in magical realism, and how music or literature can be incorporated as a basic form - a structure within photography.”

“I’m interested in how a photograph looks, one of the things I love about a photograph is how people forget that depending what shutter speed you use, you can leave things out just by letting less light in. Bill Brandt was passionate about that; he could leave out half the world, not by not having it in the frame but just by not letting enough light in to show it. I’m happy to have big chunks of things missing. I love negative space, I find white negative space much harder to work with than black negative space but I do love black negative space. In my storm shots people say to me “why is that silhouetted, they didn’t look like that?” and I say no, the world doesn’t look silhouetted to my eyes, but it did to the camera. The world doesn’t look frozen or blurred but it does to the camera. I’m interested in how the camera sees the world not how I see it.”

You talk a lot about memory, especially in BTB...? (I’m cut off in mid question)

“I agree with John Berger, photography is so like memory, you open a draw of family snapshots, you’ve got all these jumbled memories, visual memories and when you look at one photograph it will spark off a memory of something else but there isn’t a time line, like maybe in literature. One image can feed off another image, that is very similar to memory. Like Proust with his smells, you can trigger off a whole line of memories just by a smell, well an image does the same. A photograph can trigger a whole line of memories about a person or a place, or something within yourself.”

For you, does memory have a visual or verbal route or both?

“Good question! I think memory is very emotional. Emotional can be both verbal and visual. When you look at Another Way of Telling it is all visual, but it’s also very emotional and I think that it’s the emotion triggered by the photograph that creates the story line. Usually it’s emotions that trigger one memory to another memory to another. The most powerful photograph is the photograph of a loved one, especially if that person has gone. You’ve suddenly got this almost physical, emotional memory in your hand.”

On our walk through the five fields, Tancock began to expound further on his ideas for controlling the display of his images and how he can weave themes throughout the exhibition. This is perhaps the revelation of our discussion.

“People aren’t taught to read images and definitely not taught to read multiple images, whereas we are taught music and we are taught literature, taught to read and it’s a crazy one for me because I reckon maybe 80% of communication in the world is visual but we’re not taught it, it’s as if it’s supposed to be picked up naturally. I think that when people look at a photograph they think it exists in front of them but it doesn’t, it exists inside their head and then they project it back on the page. A photograph has to be read and you have to learn to read images. It doesn’t come naturally, a newborn baby doesn’t see an image it just sees the ink on paper. With any image you can misread it, and people do.”

“Once we realise that we have to read images then we can take that a step further and ask how do we read images in conjunction with each other? All I’m doing is trying to carry on the baton for people like John Berger who thought of these ideas; I’m not nearly as important as they were. I think these ideas are great, but unless you put in an enormous amount of effort, or you’ve read John Berger, then it’s not going to hit you straight away. So my idea was to find helping hints, so I started looking at music. In music you have rhythms, or you have a refrain that keeps on recurring. So I would have a shape that’s not physically to do with the image, the shape of a curve, the line of sheep in a field, followed by the same shape running through a plough line, running through some geese flying through the sky. I use that refrain to draw a person down through that series of images and those images can have other images that are connected to those running along them. You’re trying to say to people stop looking at this as an individual image, forgetting it and moving on to the next individual image, there is something connecting them. And if those refrains jump out and make you look like that, then maybe you’ll look for other connections. It may not work, I’m not saying it’s going to work, but you’ve got to try.”

“So I started photographing the same bush, over and over again, which has been done a thousand times before by photographers but what I can also say is that I can photograph the same place again and again but from lots of different aspects, if they are grouped together and people have already started thinking about groups of images, then they’ll start looking at a more complex way of doing that in a new light rather than seeing them as a jumble of shots. Rather than seeing the photograph of the gate with the birds flying up, seeing a photograph of the birds flying up, it’s not it’s a photograph of the gat

e. Things happen around gates, gates have lives; I want to photograph those things that happen. It’s not sterile land where the gate just sits on it’s own all the time. What I want to do is show lots and lots of different aspects, but if I’m going to do that I’m going to have to help people to try to understand what I’m saying.”

Do you think of yourself as following in the Romantic tradition?

“Oh definitely! But not as we think of romance nowadays. John Clare was a Romantic poet, but he was also a scientific poet in the sense that much of the information we have about flora and fauna in his period was because he wrote poems about them. He wrote poems about them in their environment. A naturalist once said, “Romanticism is about finding the relationship and the way things live together”. Now that might be a field with a tree in it, now how do the field and the tree relate to each other?

A scientist will just look at the tree whereas a Romantic will look at how they live together and how I the viewer interpret it, the story I weave round it . John Clare documented orchids, he gave them addresses, but it wasn’t a Latin address or a geographical address, it was “Mr Blogg’s back garden” or “the meadow thatused to be common land, but isn’t any more” and it was all about how things lived together, how everything is intertwined. So that’s the sort of Romanticism I’m interested in, not the Disney sort of romance, or the chocolate box view of nature. It’s a Romance of the history of that gate, or how that gate has come there, what happens to that gate. That’s why I get so bored with landscape photography, there’s no Romance in landscape photography, its all composition, calligraphy. They try to make it romantic by taking sunsets. That’s crazy, that’s not my idea of Romance. I’m very much into the way the past and the present intertwine and how they can be seen in each other and that is Romantic. I’m also interested in the way a hedge has grown into the shapes it has because maybe at one time it was layered or it’s been confined. Like I said I’m interested in folk tradition, I’m interested in myth and local tradition.”

A scientist will just look at the tree whereas a Romantic will look at how they live together and how I the viewer interpret it, the story I weave round it . John Clare documented orchids, he gave them addresses, but it wasn’t a Latin address or a geographical address, it was “Mr Blogg’s back garden” or “the meadow thatused to be common land, but isn’t any more” and it was all about how things lived together, how everything is intertwined. So that’s the sort of Romanticism I’m interested in, not the Disney sort of romance, or the chocolate box view of nature. It’s a Romance of the history of that gate, or how that gate has come there, what happens to that gate. That’s why I get so bored with landscape photography, there’s no Romance in landscape photography, its all composition, calligraphy. They try to make it romantic by taking sunsets. That’s crazy, that’s not my idea of Romance. I’m very much into the way the past and the present intertwine and how they can be seen in each other and that is Romantic. I’m also interested in the way a hedge has grown into the shapes it has because maybe at one time it was layered or it’s been confined. Like I said I’m interested in folk tradition, I’m interested in myth and local tradition.”

“ You know, in documentary photography some people want to be a fly on the wall. I’ve always believed you can’t be a fly on the wall. I am more than happy with the idea that as soon as I walk into that field I change everything. I’m photographing cycles in a way. There’s my own cycle (beating my bounds), also the seasonal cycles but I’m also photographing the cycles that the animals have, they beat their bounds. So the magpies, every evening they sit in that Elder bush and every morning they sit in the other one but I’ve never seen them do the opposite. I love the fact that I have this ritual of walking the boundaries and the animals have their rituals. I walk my boundary and the fox walks his boundaries and our boundaries intersect. I like that aspect of it and again that’s Romantic. Its not very scientific, its part of understanding the environment. John Clare said it’s no good catching a butterfly, taking it into a lab and studying it; you need to study it in the field or where ever it lives. There’s a composition that I use a lot, where the fox is in the image although he’s a tiny speck really but that’s him in context. So many wildlife photographers don’t do that, they zoom in on the animal, it’s like catching your butterfly and pinning it on a board, no Romance!”

So what can we learn from a man who admits to, at the very best, working marginally outside the landscape genre? Firstly, the documentary approach gives some great insights into both ideas and techniques, that can introduce far more originality, complexity and far more of ourselves and our interests into our work.

Secondly, Tancock’s localism, his found passion for what he already knows and loves, should give us all pause for thought. I can hear the refrain of “but where I live is boring” coming from a thousand minds. But it’s not as if those five fields he uses for Beating the Bounds are anything remarkable, quite the opposite, I’ve seen them, they are as unremarkable as any fields you have seen anywhere.

And what of the restrictive methodology, the constraints and barriers he uses? We can learn from them that there are indeed ways to break the conventions we all carry with us in our heads. He has found himself forced to make images out of what he finds in front of himself and created a body of work that is magical, elegiac and unique. But they also serve to shine a light on landscape photography, documentary photography and many of our preconceptions, to find them wanting. Could it be that light also shows a route towards a more artistic sensibility? That is a question I’ll leave you to make up your own mind about.

You can see more of Chris Tancock's work at http://www.christancock.com

His next confirmed exhibition will be at the Cloister Gallery, St. David's Cathedral June 7th -20th

There is another joint exhibition as yet unconfirmed where he may show some of his new farm project images. Check the website for details.