Master Photographer

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

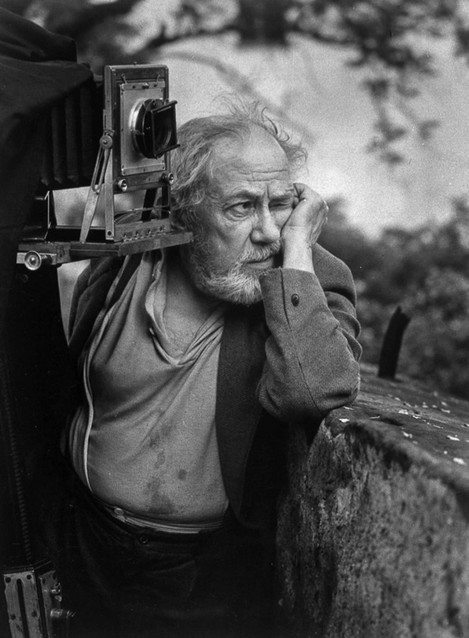

Josef Sudek may not be known as a landscape photographer, much of his work was still life, urban, occasionally portraits and quite often commercial commissions. However, his passion was very much about the natural world, his first award-winning work was for a landscape after all. During his life, he would travel a creative path through various genres but toward the end, he would return to his love of the landscape with two of his most memorable projects.

Josef Sudek lived in perhaps one of the most unstable times and one of the most unstable countries of the 20th Century. Born in Bohemia (part of today’s Czech Republic), Sudek was originally apprenticed to a bookbinder and it was his sister who was to become the photographer. The first world war put all of this on hold and although at 20 years old he was using a camera alongside his soldier colleagues and producing small portfolios, these were mostly mementoes of his experiences on the Italian front. The following year he became a victim of friendly fire when a grenade left shrapnel in his right arm which was amputated a month later.

After his convalescence where Sudek passed his time taking photographs of his colleagues at the hospital, he received a disability pension and had to consider a future career. He was now unable to go back to his bookbinding, although he latterly admitted he never had a great talent or desire for it, his passion for photography lead him to ignore the usual path into a desk job and instead, he started taking photographs and taking the occasional commission.

The problem with this was that he was not allowed to work as a photographer without having a trade license which required training. Fortunately, the proprietor of the veterans hospital saw something in Sudek’s indomitable attitude and introduced him to the local camera club where he had access to a darkroom and who awarded him a scholarship to the College of Graphic Arts where he studied art and photography.

Sudek’s attitude got him into occasional trouble and you’ll probably be unsurprised to learn that after a few years in the local camera club with his friend Jaromir Funke, where he regularly submitted images to competitions and won a landscape prize, they both ended up being thrown out over strong disagreements with the older members. They subsequently started their own club.

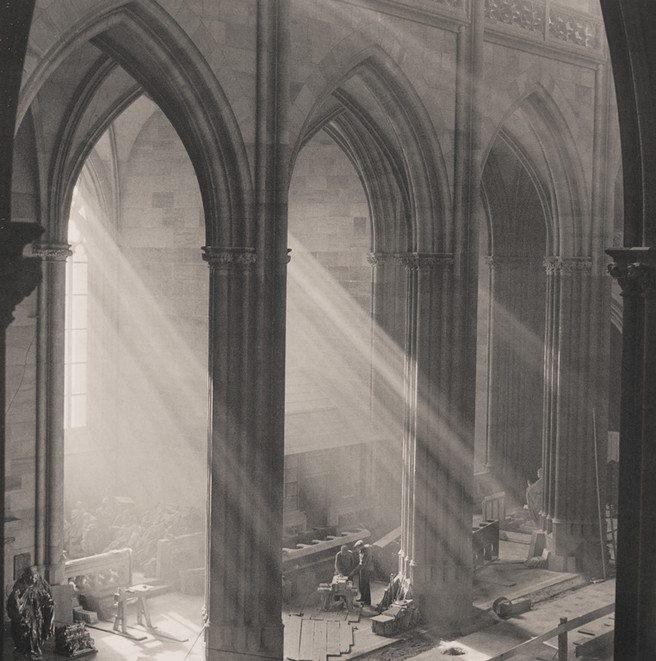

Shortly after graduation, Sudek started submitting his work internationally and began work on what was to be his epiphanic project. The story goes that Sudek entered St Vitus’ Cathedral during the final years of its construction (Despite having begun construction hundreds of years previously, the work had never been completed). Sudek was struck by both the awesome nature of the architecture and the quality of the light beaming through the massive windows and being caught in the dust from the construction works. Many of his projects included elements of this sense of light.

This is the background to the start of Sudek’s photographic trajectory but it doesn’t particularly tell us a huge amount about why he is the photography that he is. After all, much of his work is quite ‘romantic’, using elements of beauty at a time when the majority of the art world had a completely opposite flow.

One of the biggest reasons for Sudek’s position in history is that he spent a lot of his time interacting with painters, musicians and other photographers who had quite different points of view when it came to art. His closest friend, Jaromír Funke, was quite the opposite in artistic outlook to Sudek. He was a big proponent of constructivism (an approach that tried to bring the utility of construction to art - make art useful and connect it with the developing world - see Rodchenko and Moholy-Nagy) and surrealism (an approach that detached the artist from reality and connected with dream or subconscious as a new real - see Man Ray and Duchamp) and would ‘butt heads’ with Sudek on a regular basis. However Sudek’s natural inclination toward beauty and the romantic nearly always put a different spin on his work.

However, just having a friend who espoused these thoughts was one thing but he gained a contract with a publishing house and was commissioned to produce advertising. He then used his understanding of these modern ideas in the production of work that fitted in the genre. In addition to this, he would have been exposed to many other photographers and artists whilst working for the publishing house. He also worked in copying artists paintings and instead of payment would request a painting. In doing so, he became quite an art collector and developed a relationship with many national artists. All of these additional influences could not help but affect his own personal work. However, apart from some of the images in his “Studio Window” series, most of Sudek’s work that we see in books and exhibitions comes from after the second world war.

This doesn’t mean that he wasn’t successful in his work though. He regularly submitted work to national and international competitions and exhibitions and appeared alongside Steichen, Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy, Rodchenko, Brett Weston & Kertesz in an exhibitions in Prague in 1933 and 1936.

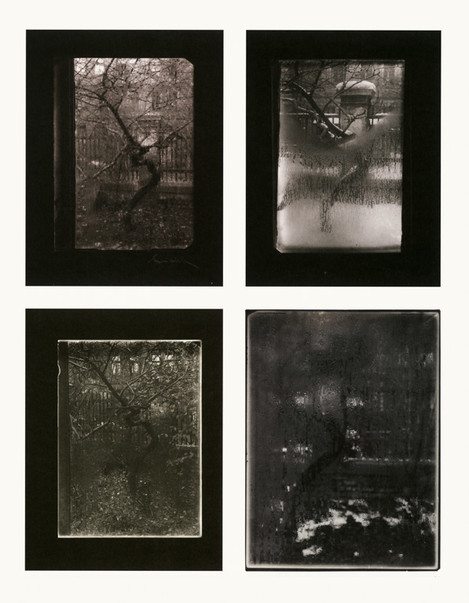

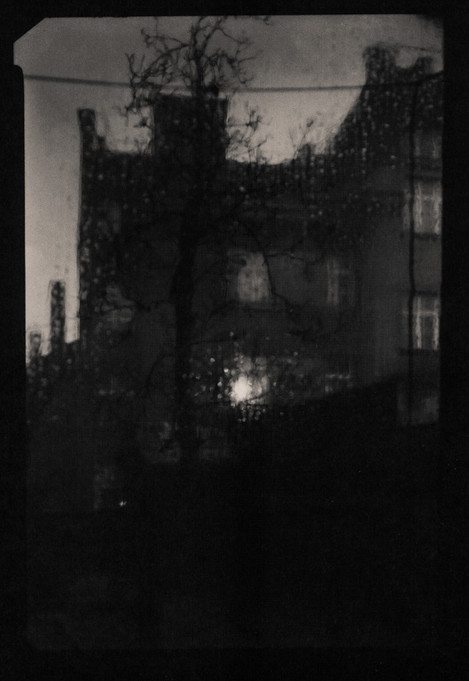

During the second world war, Sudek retreated into himself a little. He no longer had the amount of commercial work due to the occupation by Germany, he could no longer work freely in the streets and many friends left in 1939 at the start of the war. He lived at home with his Sister (also his assistant) in a small gloomy studio and started work on his “The Window of my Studio” project. This was a literal and metaphoric boundary between inside and outside spaces, confinement and freedom. He went on to produce many works in this series, from 1940 to 1976, and also changed from enlarging pictures to contact printing (recognising the clarity and rich tonality that was possible in an exhibited contact print), using various sized cameras to produce variety in the final print.

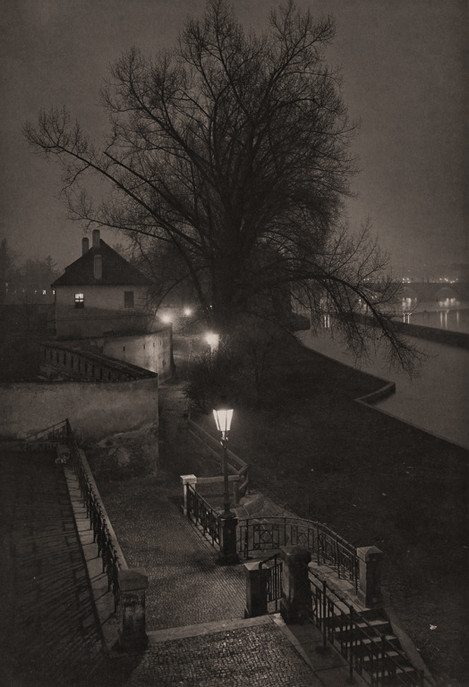

He was also limited in how he could travel, the occupation imposed curfews and blackouts and so Sudek started to take images in the style of Nocturnes, which he would certainly have seen from photographers such as Steichen and were a popular theme in pictorial photography. Sudek’s images were more ‘straight’ than the typical pictorial Nocturne though, more in keeping with the f/64 group and Photo-Secession.

This war period acted as the catalyst for Sudek’s most famous works and after end cessation of hostilities, the opening of the city brought him out of his studio and began the work that made his fame, apart from one final note. During the period from 1945 to 1949, Sudek worked mostly around Prague but also started working on other projects such as “A Walk in the Magic Garden”, “Memories” and “Labyrinths”.

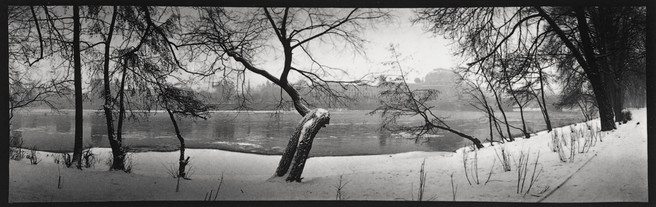

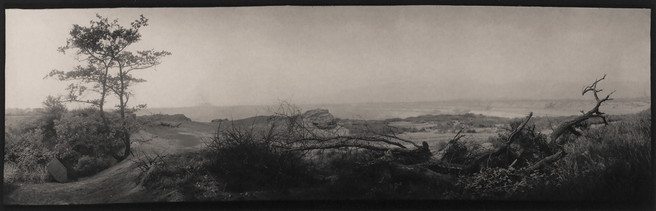

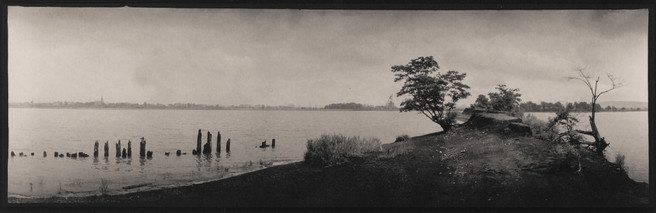

It was in 1948 that a major piece slotted into place for Sudek. Two friends gave him a panoramic camera, more specifically a Kodak No. 4 Panoram. This camera took 3:1 ratio film at 12” by 4” and used a sweep lens that covered almost 120 degrees which works out as a 11mm equivalent. However, because it uses a ‘sweep’ lens, it behaves more like stitching a panorama together from multiple frames, hence you don’t get any edge distortion that you would with a rectilinear lens.

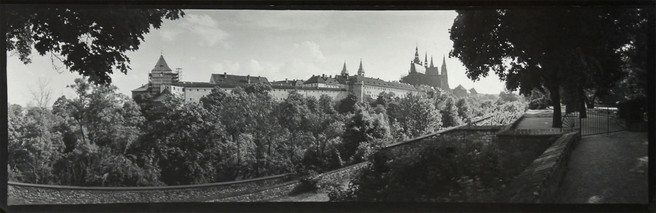

This new way of representing the world struck a chord with Sudek. He immediately started using it in Prague itself. He had already been working on a strong visual record of Prague and this new approach allowed him to create an interpretation, rather than a record of his city. At the same time he was approached by Jan Řesáč with a commission to photograph Prague for a book Jan would act as editor for many more of Sudek’s books in the future.

The coincidence of these two events led Sudek to create the work for which he is most known. Prague Panoramic, which would not be published until 1959, is as much a love letter to the city that Sudek called home as it is a coffee table guide book. Sudek’s use of the panoramic camera and his passion for light and composition produce as close to an intimate view of a large city as it is possible to create. It is also a great book to study how to compose using a panoramic camera. The 3:1 ratio is close to the 6x17 format camera that remained popular into the 21st century and which can be incredibly difficult to use in creating ‘complete’ compositions. That Sudek was able to do so without a viewfinder (the small prism on the Kodak camera only showed the central third of the image) is, even more, testament to how he made this format his own.

At the same time as he started this project, he also began many others. The following section talks about a few of his main projects.

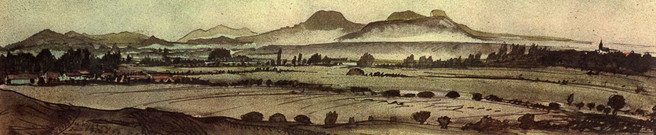

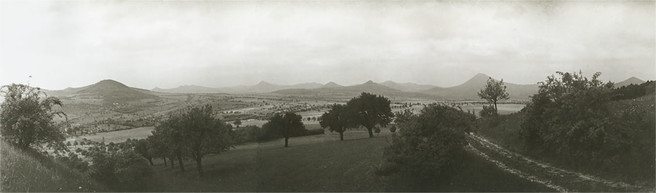

České Středohoří

The painter Emil Filla invites sudek to stay in a manor at České Středohoří in the Central uplands of Bohemia (Northern Czech Republic). Both artists work on panoramic compositions, it’s difficult to tell who inspired who but the work has strong similarities and as they were very good friends since the 1920s (they are sometimes referred to as the Alchemist [Sudek] and the Magician [Filla]) but some research suggests that Sudek’s use of the Kodak Panoramic camera was an inspiration to Filla.

Mionší Forest

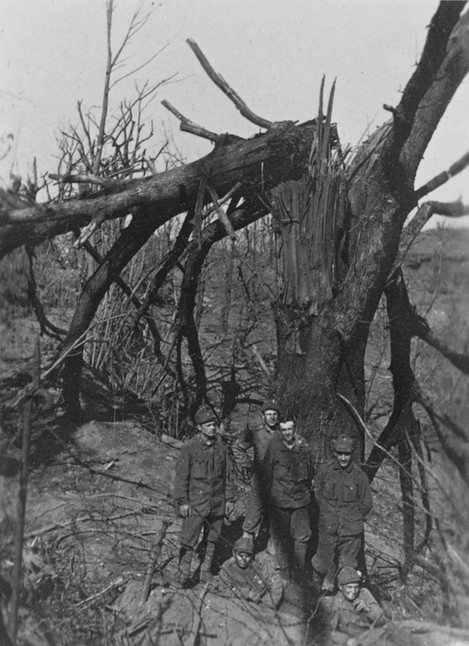

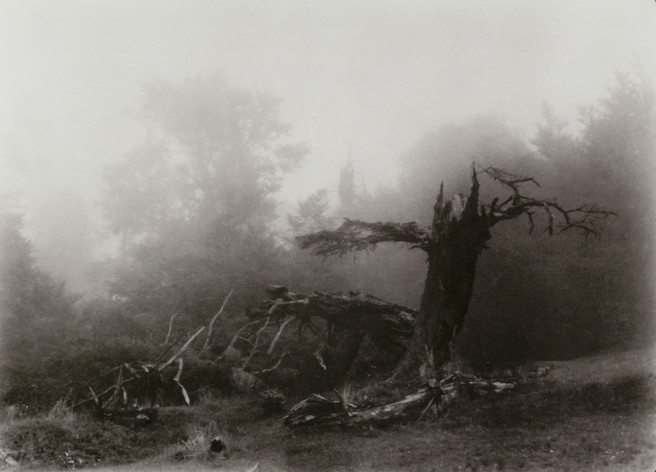

Sudek wasn't a great traveller and would produce the vast majority of his work in and around the city of Prague. However, he would visit some of his friends and early apprentices in the city of Frenštát (where he was given his panoramic camera) and after a couple of visits he was taken to the Mionší forest in the Beskid mountains. The work created in this forest was to become his longest running project and he never considered it complete in his lifetime.

He found a sense of peace in the forest and it was said that he saw something of his own injuries in the "Vanished Statues", those sentinel like bleached and ancient firs standing in a clearing near the top of the forest.

Still Lives

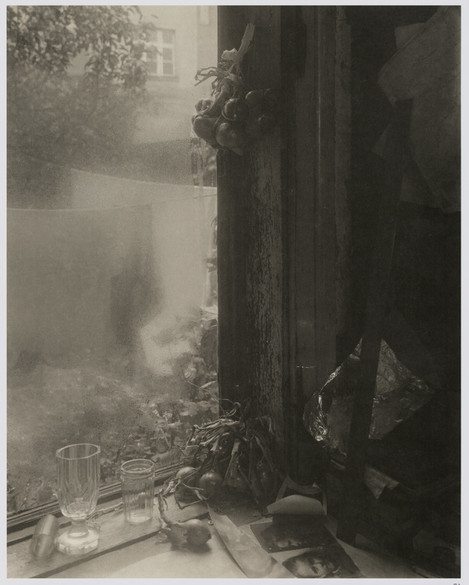

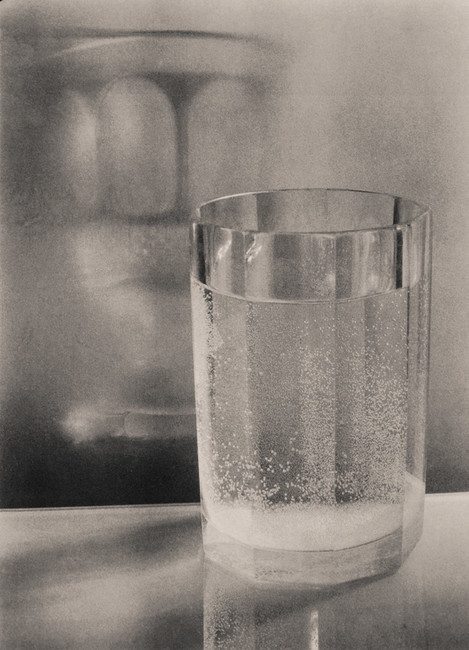

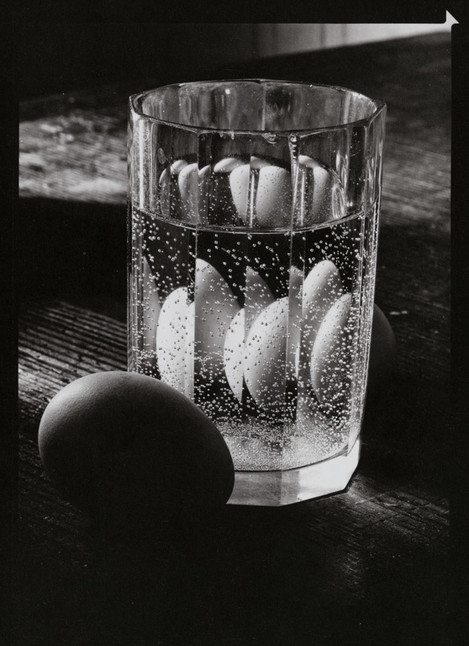

Sudek would often work with material in his studio, sometimes on commission but in later years as photographic exercise and investigation. His still lives were undoubtedly inspired by his large collection of paintings, books and by his relationships with painters in Prague. The most memorable still lives are those where the quality of light plays a significant role. Many of the photographs include a particular drinking glass with multi-faceted sides which he spent many years representing as a foil for the window light in his studio and for the way that liquids, bubbles and age moderated it.

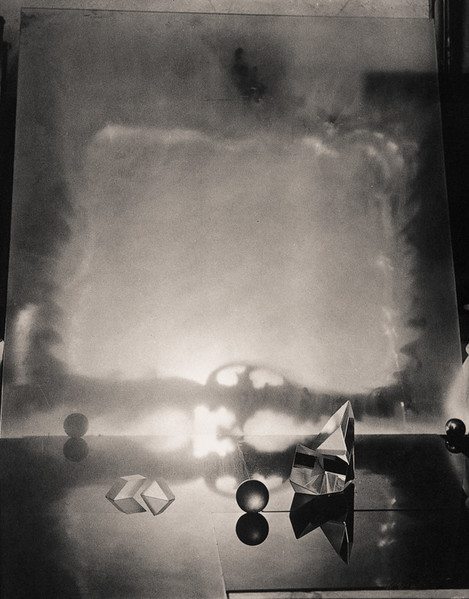

Labyrinths

Complementary to his reductive and ordered still life work, Sudek also regularly captured the disorder and detritus of his home. Wrapping papers, old film boxes, string, newspapers and letters and much more. The renaming if the clutter in his home to 'labyrinths' bestows intention and discovery onto these works. Starting in the 1960s and continuing through to his death, the works became a way of finding meaning in the everyday surroundings of his life.

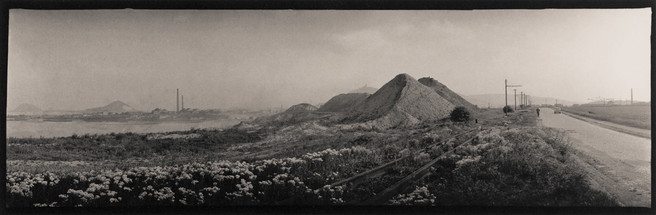

Sad Landscapes

These are some of my personal favourites of Sudek's works. In the 1960's to 1970's Sudek returned to the area near České Středohoří but this time to document the effects of the mining activities in the Most region. It was a serious crime to criticise the state at the time and hence many of the works created were never exhibited and Sudek talked little about the reasoning behind the works but it seems clear that he was moved by what had happened to the landscape and intended to represent this in some way (even if he couldn't see a time when he would be able to bring it to the public). The panoramic camera records the landscape perfectly, broad sweeps of a scarred terrain with an implied sense of beauty that once was. A book of these works was published after his death and remain a quite contemporary body of work predating many 'New Topographic' works.

If you wish to find out more about Josef Sudek's work, we can highly recommend the following

Torst editions documenting his projects - http://www.sudekbooks.com/

The Intimate World of Josef Sudek

Praha Panoramatika (Prague Panoramic)