The Advantages and Disadvantages

Richard Childs

Richard trained as an Orchestral Percussionist in the 1980's but his true love has always been the outdoors and particularly mountain environments. Throwing in his drumsticks to become a full-time photographer in 2004 he continues to work with a large format camera alongside digital equipment and exhibits his work in solo and group exhibitions as well as at his own gallery in the Ironbridge Gorge. Links to Website and Facebook

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

Many photographers would be forgiven for thinking that large format cameras are a throwback of a bygone time of stove pipe hats, frock coats and handlebar moustaches and that they have no place in a modern photographers toolbox.

However, a look at some of the most prominent photographers in the world reveals a significant minority still use film and many of those also prefer to capture their compositions using said unwieldy contraptions.

This series of articles, by myself and Richard Childs, take a look at why these cameras still attract an interest despite the many hurdles they place in front of the photographer and how you might learn to get involved in this very rewarding method of capturing images yourself.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Large Format Photography

So, let’s start with a list of problems associated with large format photography before we get on to what real advantages they provide.

Unwieldy, Slow and Heavy

There is no arguing that fighting with an upside down image attached to a device made up of gears, clamps and bellows is not something that promotes a speedy and efficient image capturing experience and many an opportunity can be lost because of this. On top of this, most 5x4 cameras start at around 3kg and 10x8 cameras 5kg plus which really means tripod use only and they can be a pain to carry around.

Composing via a Dim and Upside Down Image

With no mirror to turn the image the right way around, most large format cameras necessitate composing on an often dim ground glass with an inverted representation of the outside world whilst working under a dark cloth in order to see properly.

Expensive Film and Developing

Unlike the ‘free’ photographs you take with your digital camera, each colour image captured with a large format camera can cost approximately £10 for 5x4 and £25 for 10x8. Black and white is cheaper and you can develop your own to bring the price down to a few pounds but this still acts as a major barrier to image capture.

So what are the big advantages to large format that compensate for these quite significant disadvantages? Well, there is the image quality, which we’ll come back to in a moment, but here are our positives.

- Slow and heavy

- Composing upside down under a dark cloth

- High cost per photograph

Yes, that’s right. The negatives are actually part of the positives. How can this be and am I just making excuses for large format?

Slow and Heavy

The cameras are slow and heavy and hence they provide a disincentive to getting the camera out. What this means is that you are forced to find your images without a camera and you will spend substantially more time looking for images (instead of trying to capture photographs that aren’t quite working). I know when I am out with a digital camera, I often end up working on compositions that I know won’t make the grade and I would be better off spending time looking for better possibilities elsewhere. Even though I know this, I find it very hard to change my behaviour. Using a large format camera forces you to work like this and it may not produce a lot of images but it does promote making decisions whether photographs will work in the field, rather than at home in front of your computer. It also forces you to predict opportunities rather than react to them and to spend more time honing each photograph before pressing the shutter. This might not work for everyone but all of the large format photographers I have spoken to (and most still use digital cameras as well) agree that this is a major part of the allure of large format.

Composing Upside Down under a Dark Cloth

The advantages of composing upside down have been talked about many times, Joe Cornish is a particular proponent of using this method to assess the balance of your pictures whilst post processing. For people new to large format this may present a real hurdle but our brains do adapt and most people I have spoken to suggest that it took them one or two months before it became almost natural to compose this way. Composing upside down removes a lot of our instinctive reactions to an image and makes us see it as a set of shapes and edges, thereby helping us make the image balance, look for flow around the image and to assess ‘dead’ areas.

Working under a dark cloth also becomes an advantage, albeit not as obvious, as it forcibly separates you from the environment and asks you to assess the image as if it were a print hanging on a wall. I have often found myself almost in a state of meditation when I am fine tuning an image on a dark cloth and it is a bit of a shock when I come back out from underneath.

Both this and the previous advantages combine into making sure you spend more time assessing the image, giving you a chance to live with it for a while before committing to the composition.

High Cost per Photograph

Just as with the advantages of the format being slow and heavy, the high cost per photograph prevents the premature exposure problem. This is something that I have seen in the field with many photographers and that I suffer from also. Once a composition is found, if the cost of the exposure is cheap or free, it is difficult not to make an exposure immediately. Once this exposure is made, there is a part of me that says “I have that image now, I should try something different”. With the cost of exposure so high, you are forced to take all steps to ensure you have the best capture possible preventing that all familiar regret, “I should have done this, I could have done that” when you get an image you like on your computer but didn’t spend enough time on it.

Image Quality

I have written a lot about the image quality of large format and the articles in On Landscape have become a reference study on the differences between the resolution differences between film and digital. I won’t talk about resolution at length apart from to say that 4x5 can achieve approx 80 to 100mp and 10x8 from 100-250mp and that getting these resolutions is harder in practice than it would be with the equivalent digital of the same resolution. For more about resolution see the Big Camera Comparison.

There are more aspects of image quality than brute force resolution though. Here is a list

Lens Quality

If we compare the quality of 35mm lenses and large format lenses we quickly realise that nearly all modern large format lenses outperform the film they are recording on. For example, when I started working in large format I was lucky enough to get hold of a 150mm Rodenstock Sironar S, widely recognised as one of the best large format lenses available. When I was commissioned to take battalion photographs for the Army, I decided I needed a backup camera and lens and used a Chamonix camera with the cheapest Schneider Symmar lens I could find - £50 for a very tatty example on eBay. When I got the first test frames back I was shocked to find I couldn’t tell which was which.

In addition, the ‘corner problem’ that plagues many 35mm wide angle lenses (chromatic aberrations, coma, spherical aberrations, etc) is completely missing on most modern large format lenses. In fact, many older large format lenses are free from these issues too. This is partly because the lenses are designed to cover a lot larger area than just the film size (to allow for movements) and so you don’t see the extreme corners in normal use and partly because the simpler design for wide angles (non-retrofocal) and more relaxed tolerances allow better lenses.

It would be fair to say that nearly all modern large format lenses perform as well as a Zeiss Otus on 35mm and you can get them for less than a 1/10th of the price.

Camera Movements

Most large format cameras allow much more creative freedom with camera movements than their 35mm counterparts. For example, the Canon 24mm TSE allows 8.5 degrees of tilt and approx a third of a frame width of shift.

The movements on a large format camera are most limited by the camera mechanics but it is not uncommon to be able to tilt up to 60 degrees (not that you would ever want to!) and shift up to a whole frame width. In other words, you have unlimited creative control of movements.

On top of this, the quality of the lenses means that you suffer from very little image degradation even when using full tilt or shift.

Film Quality

One of the key things that attracted me to large format initially was the ‘look’ of film. Velvia 50 had a beautiful quality of colour and tone that I was unable to achieve through post processing my digital images. Camera’s have come on leaps and bounds since then but still, the colour rendering of Velvia 50 on a great deal of landscape imagery is impossible to recreate with a digital camera and photoshop. If you like what Velvia 50 does, then you pretty much have to use Velvia 50.

The same is true for the tonal qualities and dynamic range of colour negative film. The modern version of Kodak Portra has a magical quality all of its own and is considered the reference film choice for many contemporary art photographers (and has more dynamic range than any landscape scene I have encountered)

Another big bonus for large format is the ability to switch films easily. Quite often if I want to guarantee exposure I’ll shoot a frame of Velvia 50 first and then a frame of colour negative (usually Portra 400) as it’s hard to make exposure mistakes with Portra.

The Cost of Quality

All of these attributes come at a price that is a fraction of an equivalent digital system. A second-hand large format camera setup with three lenses can be had for less than a thousand pounds. The great thing about the way that large format works is that the camera doesn’t dictate the quality of the end result, only how flexible and easy to use it is in operation. Hence the cheapest large format camera (something like a second-hand MPP or a Bulldog build it yourself kit) will produce images just as impressive as a pristine Ebony or Linhof Technikardan. More expensive cameras just make the job easier and hence more enjoyable.

Obviously, the cost of the film and developing is an issue, for instance, Portra 400 or Provia ends up at nearly £9 for a 5x4 sheet (including developing) and £25 for a 10x8 sheet. Black and white can be cheaper at £4-5 for 5x4 and £10 for 10x8.

Developing your own film

If you develop your own film you can reduce these prices by about 30% and if you use outdated film (most of my own film is more than 5 years out of date but kept refrigerated) you can often reduce those prices by about 50%.

If you really want cheap, you can get black and white film from a manufacturer like Foma and then develop yourself and you end up with about £1-2 a sheet.

Large format photography still has a lot of relevance in todays photographic world and even ignoring the quality differences, provides an educating and entertaining foil to digital photography.

Our next instalment will discuss the various and variations of equipment you need to start with large format photography.

Personal Reasons for Large Format

Tim Parkin

I started photography with a digital camera (ignoring a short period when I was 14 with a Zenith E) and quite soon after a colleague bought me Jack Dykinga’s "Large Format Nature Photography" book. I remember saying “Don’t be ridiculous - you wouldn’t catch me doing that!”.

However, it was my encounter with a print by David Ward that changed my mind. It was on a workshop in the Outer Hebrides along with Richard Childs and I remember being bowled over by not only the clarity of the image but also the clean and bright colour and wonderful definition between in and out of focus areas.

Fortunately, the course was attended by a few large format photographers and by the time the course ended and I’d been demonstrated the ins and outs and tried it myself, I was committed to selling a bunch of digital lenses and buying an Ebony large format camera.

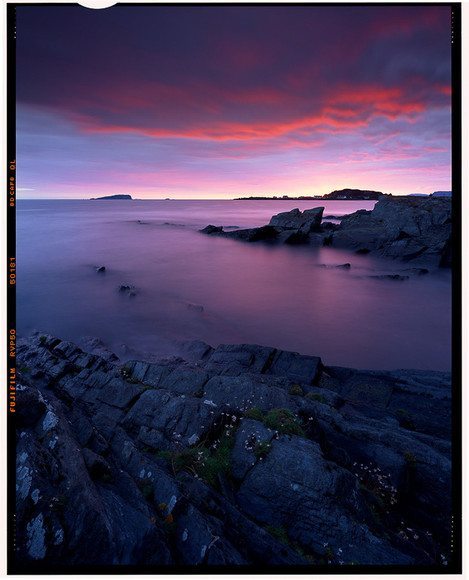

I won’t say the initial experience wasn’t rocky on occasion (I couldn’t even move the tripod in the right direction to begin with because left becomes right, up becomes down!) but I remember vividly the joy of working on each of those initial photographs on a trip to Scotland. I’ve included a few of those first images in this article.

Using a large format camera transformed my approach to composition. It pushed me to perfect each image and make sure I waited for just the right light and it also taught me to recognise when an image wasn’t going to work (there’s nothing like a few £10 photographs that look awful to learn a lesson).

Using film also taught me a lot about what good colour can look like and that is a lesson I’ve transferred to my digital photography (I now use a Sony A7R2 alongside three different large format cameras).

All of the advantages above are relevant to me but it’s the sense of craft, a working toward the most perfect artefact I can create that I really enjoy.

The one comment I get from many people is “I can take things slow with a digital camera as well!” and if someone can actually do that then all well and good. For myself, I find the ease and abundance of digital image making a difficult thing to ignore in the field - something which is sometimes great, sometimes a distraction.

Overall, large format has given me an extra dimension to image making, neither instrinsically better nor worse. It’s the manual gear shift classic car to the modern automotive experience. It’s the hands-on craft of a woodworker as opposed to a power tool production. The end result may be very similar, you get from A to B and end up with a set of shelves but it’s the journey that makes the difference.

Richard Childs

As many of you already know, my love of photography (specifically landscape) is a natural extension of my thorough enjoyment of being outdoors.

I've never been particularly interested in striving for the highest image quality and am turned off by discussion around what lens is best, how many pixels, resolving power etc. However back in 2003 I found myself drawn to Large Format only four years after picking up my first 35mm SLR.

Learning and developing the craft over 2-3 years ( indeed this is something that continues today) I feel that large format (and Scottish light) moulded me into the photographer I am today. I'm very fortunate in that my many years studying classical music gave me the work ethic and more critically the patience to allow time to develop both the technique and my style without too much frustration. I think that starting out with a film camera back in 2000 and moving up through medium format helped in this process too.

Fourteen years on and working with a large format camera brings more enjoyment as time passes. Personally, I feel that using these cameras is akin to practicing mindfulness but instead of concentrating on myself in the here and now I find myself 100% engrossed in the act of first seeking out an image and making the decision to commit or not, to the ritual of setting up the camera and attaching the lens. Then comes the fine tuning of the composition, the focusing ( both within the calm enclosed space of the dark cloth), the metering, filtration and patient wait for that right moment. Sometimes actually taking the photograph can feel anticlimactic as I emerge from my state of concentration but of course, there is the joy of developing the film yet to come.

I would sum up by saying that working with a large format camera feels like more than photography to me. I get a huge buzz being out with any camera in a beautiful place in stunning light but slipping into the ritual of large format takes me to a place of total calm that I don't experience with anything else. It suits my temperament perfectly and fulfils my needs as a photographer which are first and foremost to extract maximum enjoyment from my time outdoors on the hill.