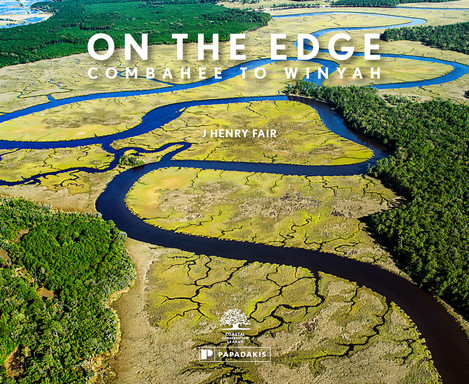

The South Carolina coast & the imminent threats it faces from climate change & human development

J Henry Fair

J Henry Fair is an American photographer and environmental activist, based in New York. His work has been featured in most major publications, including The New York Times, National Geographic, CNN, Rolling Stone and Vanity Fair. He is best known for his book Industrial Scars and its touring exhibition which has been shown around the world at major museums, galleries, and educational institutions. Fair has used his images to call attention to environmental and political problems in different regions of the world. Most of the sites illustrated in this book can only be seen from the air, either because of the remoteness of their location, or because they are hidden from the public. Depending on the political climate of the moment, Henry’s activities have aroused interest and/or curiosity from authorities. Repeatedly circling an oil refinery during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in a small plane inevitably was deemed suspicious behaviour and Henry has been awakened by the FBI in his hotel room where he has had to explain his activities. He has even resorted for, a while, to using an alias, paying cash at various flight schools and hotels, in order to avoid tracking.

Charlotte Parkin

Head of Marketing & Sub Editor for On Landscape. Dabble in digital photography, open water swimmer, cooking buff & yogi.

Back in March, Joe Cornish wrote an article about "A question of responsibility ~ Does being an outdoor photographer inevitably lead to environmentalism?". Continuing this theme we interviewed J Henry Fair, who is an American photographer and environmental activist.

On the Edge is a collaboration between J Henry Fair and the Coastal Conservation League who, in this project, bring our attention to the beauty of, and the impending threats to, our coastal regions.

Tell us about why you love landscape photography? A little background on what your first passions were, what you studied and what job you ended up doing.

Landscapes first enter my thinking from the Dutch Renaissance and parallel the rise of capitalism and the alienation of man from nature. The association with “Paradise Lost” is inevitable. Fascinating that thinkers of the time felt the implications of what was happening as it happened. I studied journalism in school.

What sparked your passion for photography?

Aside from having no skill in music or drawing, photography attracts me because it is the modern art form, and I like to make images and tell stories.

You talk about in the book your connection to the landscape in your childhood a few times in the book, one which stood out was 'Our playgrounds growing up were the coastal rivers and wetlands of the Low country'. How did this experience influence your views about the environment, pollution, etc.?

Growing up playing in nature inevitably affected my outlook on the world. Studies have repeatedly shown that exposure to nature changes a young person’s view. But it was entirely subconscious, so I can’t elucidate. But even my own images of those winding rivers and marshes make me yearn...

Why did you choose landscape photography as opposed to other genres especially the environmental activist aspect and how you've used your photography to convey the narrative about the landscape?

“The Landscape” is such a wonderful genre. As soon as there is a person or a trace in an image, it is no longer Eden. The Industrial Scars series plays with that idea especially. In the coastal series, I wanted to find some real remaining paradise. There are not many, and they are small.

Tell me about the photographers or artists that inspire you most. What books stimulated your interest in photography and who drove you forward, directly or indirectly, as you developed?

It’s important to me to study as much art as possible, both to reinspire and re-mind. One can also study it to stay current. No art is created in a vacuum, we are all responding and commenting on the predecessors whose work we admire. And my favourites change. Being in a time of great technological change, I often look to Dürer as one who understood and utilised the rapid technological changes of his time.

Other favourites in the visual realm would certainly include Giacometti, DeChiricho, Canaleto.

Your previous project and book 'Industrial Scars' explores the detritus of our consumer society which has gained a lot of exposure. How did this influence your next project? What knowledge or reflections did you take from this?

In imagining my next project, I wanted something timely and relevant that would logically follow from the last, and even intersect. I do love aerial photography, though that is by no means my speciality or only focus. But it is a great way to look at the world and show viewers something they have not seen. And it allows the creation of wonderful abstractions from landscapes. I quite like that the Coastline pictures have the same abstract quality as the Industrial Scars, though they are of course both landscapes.

"Comprising less than 10% of the United States’ land area, coastal counties house 39% of the US population and are responsible for 45% of its GDP." With this and the impending climate-induced changes in mind, you have undertaken an ambitious portrait of the coasts of the USA." Tell us a bit about the project and the first chapter 'On The Edge: From Combahee To Winyah'. What inspired you to choose this as the topic of your next project?

How did the project evolve? Did you have to refine the vision of what you wanted to achieve?

After the success of Industrial Scars, I was thinking about what project could follow it logically and stylistically. The general lack of climate crisis preparedness in the developed world, and the population migration toward the coasts, precisely when we should be moving away gave me the idea to make a project of the topic.

How did you go about researching the locations in the book?

In fact, since the objective is to photograph all of the coasts, with this project, I fly first, then research specific facilities afterwards.

A lot of the images are taken from an aeroplane - what were the challenges of aerial photography? How did you plan the trips?

Shooting from the air is exhausting, mentally and physically. One sits for many hours in a cramped jostling seat, twisted in an uncomfortable position. One of the greatest challenges is dehydration, due to the limited intake of fluids as the result of having no bathroom. How long I shoot depends on how much there is to shoot, and how far we must go from our launch spot to get there. One can spend a lot of time circling over the location to get the right shot, especially if it is windy.

Weather and season are determining factors as well, in the south, it’s hard to get good shots in the summer, and it’s bitterly cold shooting in the north from an open window in a plane in the winter.

How did you decide on the mix of aerial and ground based photography?

The mixture of aerials and terrestrials was organic. Some of the stories could only be told with a ground-based image. And sometimes luck presented a picture that demanded inclusion.

You say in the book 'Photography is about telling stories, and it’s the narrative that interests me, more than the technical aspects of the medium.' What was the overarching stories or narrative that you wanted to convey to the reader?

The primary story of this coastal series is that the ocean is rising at an ever-accelerating pace, and we need to prepare now. Natural systems absorb storm impact much more effectively than built structures, and much of our infrastructure is on the coast and must be moved. Doing so in a timely organised way will be much better than doing it in haste. There are local stories in this, the first book of the series: the impact of rice agriculture and enslaved peoples in shaping the South East USA coast, and the distorting effects of antiquated building codes and planning board which are susceptible to monied interests.

"That the essential Charleston endures is remarkable, in a city that has been destroyed and rebuilt so many times. War, fires, floods, earthquakes, and hurricanes have ravaged it periodically throughout the city’s long history" Do you see this book as a record of how the landscape around Charleston and South Carolina currently is before any further substantial changes to the landscape? Is it a historical milestone or a call to preserve?

Change is inevitable. An orderly, considered response is preferable to panicked retreat. This book is both a look at the past and present and a call to preserve the natural systems on which we depend.

"Two of the state’s most valuable bird breeding sites are in such estuaries: Deveaux Bank and Bird Key Stono, small islands in the mouths of the North Edisto and Stono Rivers where many species of birds flock to feed and mate. In the process of creating this series, I tried to record every inlet in the state." You documented the inlets in the book, how did you research these and plan the trips around them?

The intersection of river and ocean are critical historical places for human settlement for so many reasons: food, transportation, resources, waste disposal and water for myriad purposes. But they are also critical breeding ground for many species, which needs often conflict with human uses. I keep a thorough database of what I'm shooting, so it was easy to check off the inlets against a chart.

Many photographers have stopped adding locations to photographs but you have included detailed map coordinates for each photograph. What was the reasoning behind this and was there any worry about sharing locations?

I guess the reason some photographers withhold location information is so no one can go back and take the same picture?

Many of the locations in the book are inaccessible except by boat or air, and it seems that this series is very much about geography, so I wanted to make a specific place a part of it.

Were there any of the locations that you found particularly challenging to photograph?

The most difficult image was actually 1,000 images and did not make it into the book.

I had the idea to make a continuous panorama of the coastline, stitching together a consecutive series of pictures taken as I flew at a constant speed and distance up the coast. Prior consultation had indicated that the post-production could be done with artificial intelligence. Sadly that proved not to be the case. So we assembled the 1,000 pictures into a continuous picture that wrapped around the exhibit space, about 325 linear feet.

Interestingly, it is a piece of art that only works in an exhibit context. The confines of a book or internet would render it meaningless.

Photographically, what most surprised you about the project?

What surprised me the most about my idea, was how hard it is to tell any story well. One must be always reexamining one’s starting point. A third of the way into this project I started to get a collection of beautiful abstracts of wetlands and rice fields. They made a nice series and logically followed my “Industrial Scars” series.

But then I realised that it did not tell the story the way it had done in that previous series. And of course, someone else had done it very well already.

Tell me what your favourite two or three photographs from the book are and a little bit about them.

One of my favourite places in the world is one of the largest undeveloped areas on the USA east coast. The ACE Basin is named after the conjunction of three rivers: Ashepoo, Combahee, and Edisto, which join to form St Helena Sound. Their sinuous shapes are so calming.

Growing up as a child of the south entailed accepting the dominant narrative about the history of slavery and the disastrous Civil War, which was a masterful historical revision.

This picture, of a hurricane-proof building in the middle of a rice field for safe containment of the enslaved people forced to work there, exposes that falsehood. I have digitally removed the modern buildings built around the structure.

This fragile piece of land is called Captain Sam’s Spit which provides crucial habitat for many nesting and roosting birds and is one of the only places where bottle-nose dolphins strand-feed, aside from being an essential recreation area for the region. Of course, developers want to build expensive houses and have battled the Coastal Conservation League in court for years. I like for my pictures to be catalysts for change.

4282-135

The introduction was by Dana Beach Founder and Director Emeritus of The Coastal Conservation League. How did you decide to collaborate with this organisation?

The Coastal Conservation League is a very efficient and effective organisation with which I have worked for many years. More than once I realised that I was photographing the beautiful, special places the CCL had been working for years to save.

How did you manage the flow of the book with the images and the narrative?

It was a difficult problem how to create the order of the book and then I discerned the essential elements in the story, and it fell in to place.

Did you manage the project yourself or did you work with an editor?

Alex Papadakis and the Conservation League both provided essential input along the way.

How did you decide on the format of the book e.g. size and paper, print type?

They convinced me that smaller was better in this case, and I must say I like the result. I’m a stickler on image quality, but design elements I leave to pros that I trust, like Aldo Sampieri.

Where was the book printed and how was the experience of working with a printer?

I love the printing press. In our romance with the virtual world, we forget that it was the first mass-communication technology, and far more disruptive. This book was printed at a Tennessee. In the end, they did a good job. I was travelling and missed most of the trauma.

Could you tell us a little about the cameras and lenses you typically take on a trip and how you came to choose them?

In the modern world, cameras are high tech computers, and thus improve constantly. So I try to stay fluid and not be too invested in any one brand. The pictures in this book were done with a mix of cameras and lenses.

Of course with aerials, vibration is always a problem, especially when using a long lens to photograph details. For this, I often use a gyro.

What sort of post processing do you undertake on your pictures? Give me an idea of your workflow.

The largest component of my workflow is research before and after. But I am also a rigorous adherent to an efficient production process.

Everything is organised in a database, from the moment I identify my targets. After shooting, all files are renamed with a number, which remains its file name in every instance, and identifies that image in the database. That database entry grows over the years as I collect more information. The database also records every print, exhibition, editorial usage and all other information about the image and the subject shown.

If one of our readers were thinking about embarking upon a large project similar to yours, what insights and learnings would you give them?

To really tell a story, one must know everything about it, in order to understand which are the essential components of the narrative. So it must be something about which the teller is passionate, or the necessary time will be prohibitive. Also, I am repeatedly rewarded and enabled by my efficient method of storing and recalling information in databases.

What is next for you? Where do you see your photography going in terms of subject and style?

The coastline project is important to me and suddenly has developed legs. So I will continue with that. I feel a little trapped in the niche of being an aerial photographer, which just happened to be a method I used to tell a particular story. But I have learned in my life that niches are not necessarily a bad thing.

I will probably do a project on race and slavery if I can find the time from my other projects.

The book is published by Papadakis and is available from Amazon.co.uk for £45.

If you want to share your ideas or suggestions, or feel you could write or contribute a piece on what we as a community can do collectively to help the causes of landscape, ecosystems and the wild world then please do contact Tim and Charlotte (via the contact page), who are keen to spotlight what has become the issue of our time.

J Henry Fair headshot credit Dirk Vandenberk