And What it Means for Landscape Photography

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

By now, there can’t be many people that haven’t seen the other-worldly “photographs” generated by the various forms of artificial intelligence-based image generation algorithms. They’re typically of the ‘uncanny valley’ sort, almost realistic but slightly too fantasy book cover for their own good. Their progression from small objects of interest to high-resolution, realistic productions has been meteoric. But for all that they can generate ‘award-winning images’, what does their future hold for landscape photography? Firstly, what the hell is AI imagine generation anyway?

What is AI Image Generation

Firstly, a little context and background for just what artificial intelligent image creation actually means, and it’s quite different to how people might imagine it. It’s also quite disturbing because even the engineers who have programmed these algorithms don’t quite know how they can create a final image.

Most people imagine that the algorithms have scoured the internet for ‘components’ of images that they somehow composite/collage together to create a final image. This would have substantial and obvious copyright issues immediately, and the original photographers that have photographed people, buildings, cars, etc. would more than likely recognise their ‘sections’ of a final image, especially if it were publicised widely, as perhaps in the winner of the competition mentioned above.

In reality, the process of creating these images is as strange as anything I would have imagined possible from all I know about computers. Firstly, the system looks through many millions of images that have text associated with them, and it creates a ‘looks like’ database, essentially a bunch of fuzzy references that get stored in the brain of the computer (I use poor metaphors for creative effect). When it does this for many millions of images, the ‘brain’ has a system that can recognise images, and parts of images, and relate them to the text that was stored alongside them. Imagine this is a ‘savant’ child that doesn’t know anything about art or even about the outside world but can say “that curve looks like something Monet might do” and “that circle is a bit like a roundabout”, etc.

If you’d like an overview of how the two main AI image generation systems achieve these, have a read of the following, and please ask questions in the comments if it doesn’t make sense or if you’d like to know more. You can just skip this and go look at the ‘funny’ pictures below if you like, though!!

AI Types

There are a couple of main ways that AI systems work, one is called a Generative Adversarial Networks and the other is Stable Diffusion. Don’t worry – you don’t need to know these but it might help you understand some of the legal subtleties around copyright later in the article.

Generative Adversarial Network

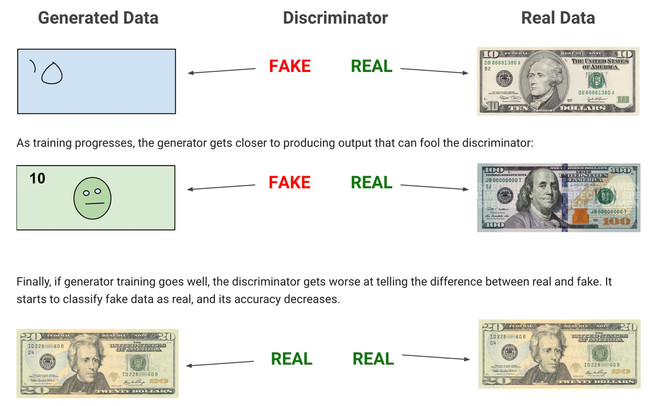

From your perspective, as a user of the system, you supply a ‘seed’, a set of words that the computer can use to target source material and/or an image that is used to add visual cues. For our example, the phrase is “ten dollar note”.

The computer then creates a ‘generator’ and a ‘discriminator’. For our purposes, we can call them a ‘forger’ and a ‘detective’. The systems then sets them against each other – this is the ‘adversarial’ part of the Generative Adversarial Network.

Now comes the insane part. The forger generates a page of colourful noise. No numbers, no shapes, just noise. Like a hippy on their first psychedelic experience, the forger then looks at this noise and says “Now you mention ten dollar note, that bunch of noise over there reminds me of a face and those squiggles look like numbers” and it nudges the pixels around to make them look a bit more like the hallucination. The end result still looks mostly like noise but with a hint of ‘form’.

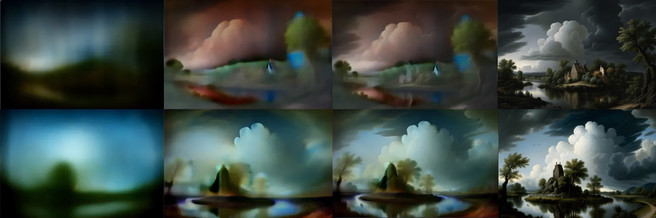

Here are a couple of pictures being generated by Midjourney AI. You can see something of the steps it takes to reach the final image. These aren't working from 'noise' but from Latent Spaces (see later in this section).

Once we have gone around one cycle, the detective then has to guess between this page of noise and an image from its data set of real “ten dollar notes” and have a guess whether the colourful noise is a real note or not. Like a savant child, the detective knows nothing about ten dollar notes but it knows when it sees something “familiar”. It guesses whether the forgery is fake or real.

But just as the forger is rubbish to begin with, so is the detective. Once they’ve had a guess, they’re told how they did they take a tiny step toward become experts on “ten dollar notes”.

After a huge number of iterations, the forger becomes a master but so is the detective. Because they were trained on lots of ten dollar note images, the results start to look more and more like what we have in our source material. But the result will be some strange combination of all the features of the ten dollar (an australian one, a canadian one, a US one, etc).

Stable Diffusion

The other common system, Stable Diffusion, uses an inverted way of working out what is needed and is, fortunately, a bit easier to describe. It takes its source images, replaces them with noise and then works out how to transform the noise back into the image. It stores these transformations for every source image.

When you provide your text prompt (or image), it takes a set of these ‘noise-removing transformations’ and applies all of them in some balanced way. Gradually the noise transforms into an image (like magic again). I’ve kept this short so hopefully you’re still awake at this point.

Latent Spaces

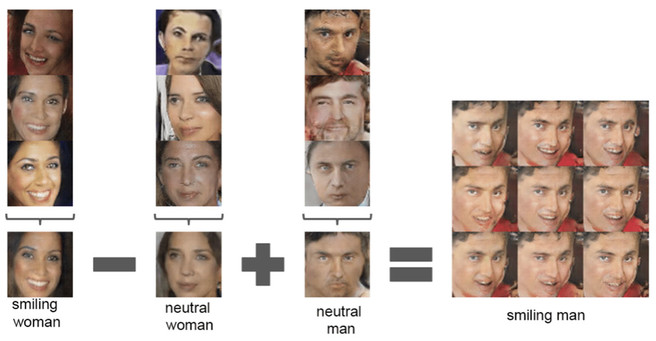

There is another aspect of both Generative Adversarial Networks and Stable Diffusion Algorithms that isn’t mentioned much. In most cases, instead of directly using the source images as a collection of pixels, they use ‘latent space’ representations of the images. The latent spaces are a way of encoding images in something other than pixels. For instance, it may use a matrix of facial features (something that is actually used as a common sub-algorithm in many AI image systems). The facial features may be eye colour, nose shape, mouth structure, head angle, etc. A picture of a face can be deconstructed into these elements and, through this, images that are similar get stored close together in this multi-dimensional matrix. Any point in this matrix space represents a unique looking face. As you move around in the matrix, the face changes, eyes getting bigger, nose shorter, skin texture changing, etc. This is behind a lot of the clever manipulations of faces you might have seen on social media where one face transforms into another.

The ’aspects’ of a picture don’t have to be descriptive in the way that our face adjectives are. It might store aspects such as shape, texture, shadows, and aspects that don’t even have words that a system has recognised as a common feature of images. It’s this decomposition of images into latent spaces that has allowed AI to be so efficient in storing and combining disparate elements (for example, a fish on a bicycle).

Either AI system can create absolutely novel views that have never existed and that don’t exhibit any strong similarity with any “individual” source image. As Asimov said, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” and this fits the bill perfectly.

What it isn’t, however, is an actual ‘intelligence’ (at least not yet). There really isn’t much that could be described as intelligent going on at all, at least not compared to human intelligence. What we’re seeing bears more in common with a savant child than a self-conscious artistic intelligence.

We’re still a long way from a system that can think abstractly and create novel ideas (rather than permutations on existing ideas). Some might say that most humans are the same, and perhaps they might not be too far wrong there. However, we’re still a long way from Terminator, SkyNet and the Rise of the Machines.

Some Examples

After an initial play at seeing how far I could push Midjourney AI into creating weird stuff (a penguin in an Edward Hopper bar, aliens playing cards in the style of Caravaggio, cats having a banquet in a red and black cave in the style of Caravaggio) I thought I’d see what it could create in terms of landscape photography.

First, lets see what it thinks is the best landscape photograph! Here’s “Award Winning Landscape Photograph”

Whilst it’s definitely a landscape and capable of winning an award, it doesn’t exhibit any aspects of 'award winning' I would wish for. So it was time to try some ‘specific’ searches. Let’s try some location-based ones first to see what it thinks of photographic areas (excuse me that these are all British).

This has definitely picked up on some good Yorkshire cues. It has the broad glacial valleys, stone walls, sheep, stone built cottages with trees, etc.

Again, the AI is picking up on location based cues and you can almost guess where photographs are from but they’re not quite right. I love how the AI thinks photography from the Lake District should be part of interior design though (reflects the targeting of art at the middle classes in Cumbira). But if you think the Lake District is all posh holiday cottages, Cornwall wants goes full interior design!

More very Cornish views, they’ve got the coastal geology right and the wide open beaches almost Marazion but also Watergate-esque etc…

I gave it something I though I might be a bit more familiar with so I'd stand a better chance of recognising things.

So Lochaber isn’t a keyword that is used very often, but it’s picked up on a more Highlands look (a bit Scandi I think perhaps). The mountains look like nothing familiar though. Perhaps "Glencoe" would be better term to use.

All of these definitely look Glencoe esque but with a flavour of Glen Etive in them. But I’m struggling to see where they are. Some of the mountains almost look familiar. It’s that ‘uncanny valley’ again.

What I think we’re seeing is that the system certainly isn’t collaging elements into a scene but it is including elements that it thinks are important. For instance, it seems to think “I see mountains in all of the photographs that are associated with Glencoe so I’ll make sure I put some mountains in” with possibly some specific types of mountains – i.e. Terraced, rocky, etc.

If we ask it to make a picture of Scotland’s most famous mountain (at least visually) things start to look a little more familiar. Possibly because of the volume of images that match this description, the mountain has a classification of its own.

Finally we can see something recognisable going on. Randomly placed trees are appearing but at least in a couple of these images you can make out the differentiation between the North and East faces.

Let’s go full ‘photographic icon’ and try Buachaille Etive Mor with Waterfall and Trees

Oh yes!! That top left one is getting pretty damned close now and even has the right bulging rocks in the foreground. (for reference, see the image from David Mould below)

I fancied the top left one done as a larger picture and Midjourney allows you to ‘upscale’ an image it has created.

Interestingly, the painting above also has a signature on it. I’ve tried interpreting it but it makes no sense. This is quite common for text and numbers on Midjourney. It has a ‘savante’ like idea of what writing and numbers should look like but no idea what they are.

Again, I spent a while seeing what other iconic locations would look like and I’ve included the following for you.

Whilst asking for upscale of a photo of Patagonia, I accidentally asked for it twice. It was very interesting to see that it copied the broad strokes of the idea but the ‘infill’ areas had lots of differences. Different peaks, different trees, clouds looked different etc.. You can see from this how Midjourney starts from broad outlines and infills things it thinks match the view.

It’s quite clear that, in order to generate something recognisable, you need to work with very popular photographic locations or ideas. For instance, if you want to ‘forge’ an amazing view of Kirkjufell with Aurora then Midjourney does a fine job

Or the Old Man of Storr at Sunset?

Or even some more abstract but iconic ideas such as “icebergs on a black beach”

Or my particular favourite, rainbow aurora and snowy sunset

Is it Art?

Well, considering the problems we have working out if human-generated work is art or not, I’m loathe even to try to answer this. And I think the answer is more tied to the human aspect than people would like to think. If everything humans can ‘create’ should be considered ‘art’, regardless of its derivative or mechanical nature, then should we consider the same for the machines, unless we define art as ‘stuff humans make’, which is absurd if analysed at any length.

If we imagine a ‘black box’ analysis (rather like Turing’s AI test) then we need to be able to look at an image with no external information and say whether it is art or not. The chances of us doing this in a way that consistently rejects all AI images is virtually zero. Hence some AI images must be art.

That is unless we define art by the stuff that came before the generation of the artwork, i.e. art is in the thoughts and actions of the creator leading up and including the act of creation of a painting, photograph, sculpture or whatever. This would really screw things up as, without knowing how a piece was created, we can’t say whether it is art.

I personally like this idea that art is a symptom of everything but the artwork; that art is intrinsic to its creator and context. This does also mean that if I generate an AI artwork and use it in an artistic context, then the AI image can become art through the way I create and use it.

As you can see, the definition of art is like a manic cat being herded into a box on the way to the vet. It wriggles and writhes and refuses to be pinned down.

I do like the fact that the birth of new technology can challenge our perceptions of things we took for granted and thought we understood.

My own personal interpretation is now that art comes from inside the artist, from connections and relationships, from influence and synthesis. Storytelling, metaphor creation, etc. I still think the artwork itself is a big part of what art is but is insufficient by itself.

In this way, the future of art is probably more connected with the artist than the artwork and, if this is true, this is no bad thing at all.

The Influence Question

People often say that AI images are overblown, gaudy and cheesy, but they’re forgetting that these AI systems don’t have a taste filter, and they have been trained on every image found on the internet. And, not to be too blunt about it, the Internet is made up of mostly overblown, gaudy and cheesy images, and we shouldn’t be surprised that the current AI results reflect that.

What will be interesting is when systems can be trained on curated data sets. All modern art paintings, the back issues of On Landscape, the highest-ranking images in art competitions, etc. Some photographers are already experimenting with using their own photographs as part of the influence data set for their local AI systems.

There are already photographers out there creating their own data sets and extrapolating from them to create derivative works.

Will it put Photographers out of Business?

There is a long history of technological developments arriving and being accused of killing existing industries. And it’s true that many industries do die out because of new technologies - but for every industry dying, new opportunities arise. The introduction of photography was originally seen with horror by the painting establishment. They thought that it was the end of painting. In reality, it was the end of photo-realistic painting for most ‘consumer’ purposes but it was the start of one of the biggest ages of development in the history of art. Freed of the shackles of reality, artists started to ask themselves, “what else can we do” and the late 19th and early 20th Century developments in art all find their seed in this moment.

So what benefits can landscape photography take from the use of AI? The first answer can be derived from the fact that the AI has absolutely no knowledge of the subjects that it’s creating photographs from, and hence each image is a standalone, semi-random creation. This means that any photographic work where the veracity of the ‘subject’ and the emotional concept is important, cannot be easily generated. Also, any series of photographs on a concept that tries to evoke a feeling or idea will still, for the moment anyway, need to be conceived and executed by a human being.

I’m sure that some way of creating cohesive photographic series may happen at some point, it will be a lot harder to create than the current single images though. (we must add that once AI becomes indistinguishable from humans, they can inherently do whatever humans can do - I don’t see this as something on the horizon, and so it’s pointless reacting to the possibility).

Also, and this is important for landscape photographers, images that depict the real world with some level of veracity will be very hard for AI systems to create without actually going out and photographing them itself. So if your photography has its foundations in creating bodies of work from the real world, you should be well placed to continue as long as you can find an audience that cares (a perpetual challenge for any photographer).

However, if your photography relies on the perspective blended, aspect ratio transforming, dehaze applied, wowalicisous visual eye candy, then you might well have met your match, even with the current generation of AI. Time to find a new niche perhaps?

So what use is AI image generation to us?

So we’ve decided that AI image generation isn’t going to affect our livelihood (despite it affecting our blood pressure when we see them billed as “amazing moments” on the Internets) What use is it to us then?

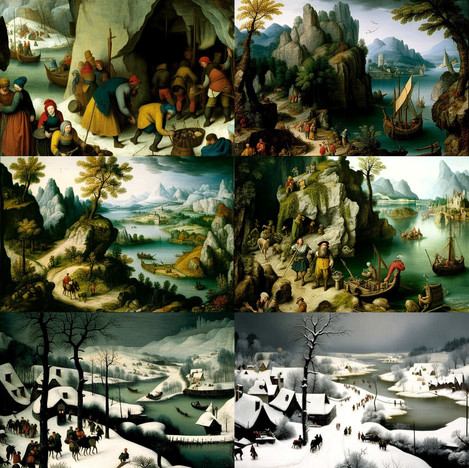

One of the biggest uses I can see is as a way of tapping the internet for ideas. I spent a couple of weeks of evenings throwing prompts at the system to investigate what the systems would generate given prompts, including various artists, living or dead. For instance, I tried generating works by Claude Lorrain and was pleased to see it producing an image that included so many of his compositional techniques. I also used it to look at Turner, Ruisdael, Bruegel etc. It was really interesting to see which elements the AI had extracted from the range of images available to it for each artist. You could easily draw compositional or tonal tips from some of these distilled images.

You could try this with photographers, but I don’t think there is enough work online for Midjourney to derive anything useful. It is entertaining to see what it conjures up and, if you apply an analytical approach to your browsing, I’m sure that some of its creations might trigger some creative ideas.

If I were a visual artist working in a more abstract sense or in mixed media, I think that the way that Midjourney conjures up creations that look like nothing you’ve ever seen before could be a fantastic way of sourcing new ideas. At one point, I had played with creating a Peter Lik view of the slot canyons in Arizona, but the work looked more like folded paper, and so I ended up working on creating standalone origami works that resembled desert canyons. If I were of a more practically artistic nature, I could imagine taking these ideas and using them as the basis of a project.

Where might it go?

At the moment, the seed pool of images is uncurated. In other words, it might have some good images in there, but it’s also full of crap. As mentioned previously, it would be very interesting to be able to pick a library of images to work from. It may be that all those skills keywording stock photographs will become useful again!

There will also, inevitably, be massive improvements in the way that you can work with images. The ability to specify how an image is laid out, ask the system to create a variation in textures, ask for specific objects (trees, grasses, etc), and supply ‘influencing’ images. In other words, be directly creative in the way a final image is constructed. There are already AI systems that allow you to make a rough sketch and they will interpret the shapes and make a scene from them (click here).

So the biggest changes will probably be in the way we interact with these systems. I can see an AI that generates a scene but also creates a 3D model that allows us to reposition the camera, for instance. Or we can manipulate items using some form of virtual reality tools - stretching mountains, for instance (oh dear). Here’s an example of just this.

For a range of different directions the Stable Diffusion model is taking, try having a look at this video from Two Minute Papers (a highly recommended subscribe if you’re into the geeky side of AI systems)

We’re not in Asimov’s World Yet

In Guy Tal’s article in this issue, he suggests that we may develop an AI robot that can travel to various locations and take photographs in a way that is ‘perfect’. An AI robot that, when told to take a landscape photograph, can find and interpret all the information on photography, interpret the perfect 2D photographs and try to find a way to position itself in ways that can recreate that perfection. That understands the cycles of weather and flora and can infer the way that secondary bounced lighting can change the way an item is interpreted by the human brain as three-dimensional. Etc.

I find this situation difficult to imagine without the AI photographer becoming so human-like that we might need to start thinking of such a machine as self-consciousness. And machines that could do something like this will be changing society so much in other ways, the fact that it might be able to reproduce an archetypal Peter Lik is essentially meaningless.

Before this happens, I can see situations where a drone can be let go, and it can go and search for compositional elements in an area using some of the visual formal devices (compositional components) and moving around to create parallax-driven relationships.

But the real answer on where this will go is “we don’t really have a clue”. When the Internet started being used, most futurists were so far out in their predictions of the possible (beyond the trivial “everyone will have access to the content of books) that it’s quite funny looking back. The same will be true for AI and image generation.

The Copyright Question(s)

The first copyright question is “are AI generated images copyrightable?”. I will be very surprised if some AI images aren’t considered copyrightable as most of them have some aspects of human intervention, and there doesn’t seem to be anything to say that the ‘prompt’ isn’t a direct creative control over the output image, even if that output image is automatially generated. It will probably take a few court cases before the law settles down, and those cases can only start when somebody ‘copies’ an AI-generated image, so it may be some time yet.

The bigger question is whether AI algorithms are breaching the copyright of the source images that it has scraped from the internet.

If you’ve read the overview of how the AI algorithms work above (GANs and Diffusion) you can see that the system isn’t really copying anything from the source images and is, in fact, acting in a similar way to how our own creativity is influenced by our past experiences. Nearly every artist in the world will admit that we don’t ‘create’ anything new, we use our own memory of everything we’ve seen to inform something new. In fact, many creatives collect printouts (or Pinterest boards) of the ideas they want to work around, particularly in the commercial world.

We may inject a small amount of our own ‘novel’ ways of working, but the vast majority of our work is a synthesis of many of our influences. So a computer generating an AI image isn’t copying the content it finds, it’s being influenced by it (for some definition of influence), and, as a human, at least, you can’t be prosecuted for being influenced by something.

It’s worth looking at a couple of the court cases surrounding the use of copyrighted source material in the generation of AI images and how the ‘prosecution’ is framing their motions.

In nearly all cases, they are trying to suggest that the AI systems actually make clever collages directly from the source material. This only makes sense as an attempt to fool a judge into a early motion in order to avoid analysing the issues more deeply. In other words, the prosecution already realise that they don’t really have a leg to stand on.

We have to remember that copyright law has legal pressure on it not to limit people who are honestly creating new art. Examples of this abound, some quite absurd. The most obvious is probably Richard Prince’s use of black and white photographs of Rastafarians where all he did is scribble or paste in a guitar and a funky face. The judges found in Richard Prince’s favour.

The open and shut case surrounding copyright is probably Google’s direct copying of images in the creation of their image search engine. If copyright allows this, then it’s hard to see how the obviousy transformative images generated by AI breach anybody’s copyright.

The images were clearly mostly copies of the originals, at least in terms of image real estate. However, the courts protected Mr Prince’s use of the images as transformative.

If this is protected, how can we possibly suggest that my picture of a Cthulu god MAGA knitted toy is somehow not transformative?

This harks back to the difference between ‘influence’ and ‘plagiarism’, and I can’t help but think of the results of AI algorithms as an ‘influence’ engine, probably more so than many humans.

Let’s say the law says that all of the images are derivative. We now have a potentially massively useful resource dead in the water (at least commercially). Plus we now have new legal precedent for claiming that transformative work could actually be illegal.

In human terms, each artwork is considered on its own terms. The artist perhaps knows what influenced them (however, there is precedent for people creating things that are very similar to things that they had previously seen but forgotten) but legally, each case needs to be handled separately and it’s up to the ‘plagiarised’ artist to sue.

There is an extra problem with AI image generators though. The end users don’t know if what has been produced is derivative or transformative because they have no clear idea where the influences came from. As a large company, would you trust images generated by AI to be ‘cleared’, I know I wouldn’t? This isn't restricted to just AI image generators though, your AI sharpening software also pulls in resources from elsewhere to 'comp in' areas of lower resolution. You didn't think all those facial details were appearing from nowhere did you?!

Epilogue

The story of AI Image generation is only just beginning and we don't know where it is going to go. Here's a couple of interesting tit-bits for you to chew on though. At the current rate of use of 'source material', AI's will run out in less than a decade. They'll not only start regurgitating the same old sources but with so much AI generated content appearing, AI's will also be eating their own creations.

Finally, AI's are only as good as image captioning and with SEO so important, images are no longer captioned for their meaning but for their commercial usefulness. Capitalism's noise is already the bane of the AI world!

QUICK ADDITION: I HIGHLY recommend watching from an artist talking about AI and art. So many good points made about what art means and how AI is actually a GREAT addition to an artists environment.