Living and Photographing in the Wilderness

David Leland Hyde

Nationally syndicated writer, keynote speaker, and a widely published photographer in his own right. Since 2006, conservator and curator of his father’s photography collection, working with galleries and museums to preserve and exhibit the historically significant work into the future.

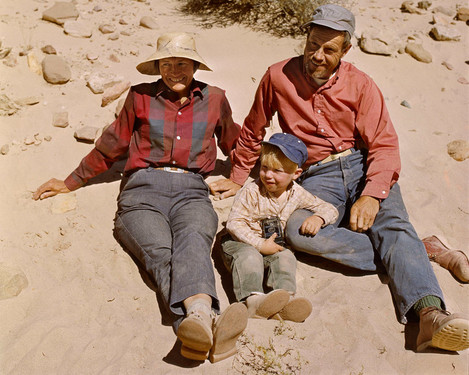

My parents, Ardis and Philip Hyde, as a team, made a full-time living in nature photography for 60-years before many others did. They also not only helped to make national parks and other wilderness, they quietly and for the most part privately, helped pioneer the Post War wave of the Back to the Land Movement. Before sustainably became a trend, they lived a low carbon, low impact, self-sufficient lifestyle.

They lived in the wilderness, which not only surrounded their home and gardens in the Northern Sierra, but also became the typical destination for professional projects, many in national or state parks. They also made a point of traveling over back roads through the wildest places possible on the way to photography locations. They often parked for the night far from any towns, perhaps in a gravel quarry, on a side road or in a primitive campground.

Though Mom grew up in Sacramento and Dad in San Francisco, both of them had roots in camping, farming and wilderness. Mom often spent weekends on her grandfather’s ranch. Also, her father took the family camping in the Sierra many times a year. Dad hiked in the hills of San Francisco, Marin County and beyond. He first backpacked in Yosemite National Park with the Boy Scouts when he was 16. He also backpacked the Yosemite backcountry with his father and brother. Part of what brought Mom and Dad together was a desire to be in the outdoors as much as possible.

Starting early in Dad’s career, going against the advice of both of his mentors Ansel Adams and David Brower, he and Mom decided to live in the wilderness, not just work there. They took up residence in the mountains far away from the photography marketplace. They acquired 18 acres with National Forest bordering two sides of the property. Dad built what was originally only a 1200 square foot home with a garage, but he added a second bedroom and a larger studio later. The house sits about three hundred yards above Indian Creek on a shelf formed by an ancient rockslide from the precipitous rock faces of the peak across the creek called Grizzly Ridge, which rises 3,000 feet nearly straight up and is capped with snow most of the year.

Dad designed, drew the plans and built the house by hand. It took him two years because he did most of the work himself with some help from Mom in the evenings. A few other friends helped pour the foundation and hoist the large beams for the roof. Everything about the home, the large fireplace made from stones from the property, the flat roof, the solar hot water panels, the clerestory windows, the raised bed vegetable garden, the fruit trees and the whimsical stone lined pond and flower garden were all ideas adopted from other pioneers of conservation and low-impact living.

Mom not only taught kindergarten full-time in Greenville, California, she also became known for her knowledge of organic gardening, food storage and preparation. She became an expert on gardening to attract butterflies, bees and other beneficial creatures in the Mountain West. She planted Butterfly Bushes, Virginia Creeper, and Japanese Maples. She was an expert plant pirate and regularly gave other gardeners cuttings. She grew 4-5 varieties of Dogwood and many other colorful shrubs and dwarf trees. She also became highly skilled at canning, freezing, preserving, making her own soap, bread, cheese, butter, tofu and many other household goods. She grew strawberries, raspberries, and rhubarb. When I was about seven, she and I planted a vegetable garden.

For better harvest yields, Dad let in more sunlight by cutting trees at the edge of the forest for firewood, leaving me to dig out the stumps. From a young age I remember hauling straw, sand, topsoil, manure, gravel, sawdust, wood chips and peat moss for the garden, as well as the winter’s wood supply in many loads in our dark green dented 1952 Chevrolet step-side pickup my parents bought from photographer Brett Weston in 1955.

He not only put in a lot of physical labor at home helping mom carve a home out of the wilderness, but photographed far from home for long months each year and sent out masses of press and show prints when he was home. He was working to get his nature photographs used by organizations and publishers before the market for nature photography had been established. However, by continuously sending out prints, negatives and transparencies, and because nobody could argue with their quality and power for illustrating nature, publishing credits and exhibitions gradually came. Also, his mentor David Brower began to expose his work and use it in the popular and widely known Sierra Club Calendars, the Sierra Club Bulletin, brochures, and other publications for many conservation organizations such as National Audubon and the Wilderness Society, as well as many more local groups all over the Western States. Sunset magazine and other expensive slick magazines started using more photographs solely of nature during the transition to color as image reproduction technologies improved. Sunset, Life and other publishing houses also produced books showing and selling the American West to new families after World War II, who were also newly automobile-mobile and looking for places to visit, explore, camp and stay in the burgeoning variety of motel franchises. Hyde’s photographs, by the end of his full-time career, had been the primary illustrations in a few dozen large picture volumes and appeared in over 80 other books.

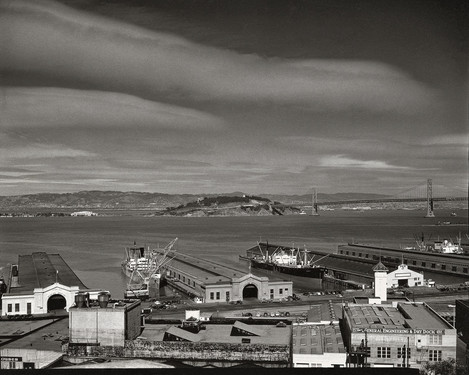

Meanwhile, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston and his sons Brett and Cole, Minor White, Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange and other fine print makers became increasingly popular in the black and white collecting art world. They invited Hyde and his other classmates and a few others who had talent in the darkroom, to exhibit with them in significant shows all over the nation and the world. White curated a solo show of Hyde’s work at the George Eastman House Museum, which led to a Hyde solo show at the Smithsonian in 1956.

From the time of their marriage in June 1947 until Dad began to lose his eyesight in 1999, he spent an average of 99 days a year in the field. Mom accompanied him the most during the months of June through August when she had time off from teaching kindergarten. Dad traveled mainly between April and October in the Western United States; camping, backpacking, driving, riding horses, mules, trains, planes and boats to access wilderness for almost one third of every year of his more than 60 years of full-time photography.

The spring and summer of 1955 are good examples of how much the Hydes traveled in Dad’s early career. Even with this level of road travel, Ardis and Philip still averaged far fewer driving miles than the average American couple. Throughout a 60-year full-time photography career, the Hydes averaged together less than 10,000 miles per year. American couples average over 27,000 miles per year.

In 1955, after buying the 1952 Chevy Pickup from Bret Weston in March, Mom and Dad put a camper shell on it, christened it Covered Wagon and took off in it from April through September. They spent the last 12 days in April over 300 miles from home in the Coast Redwoods. Next Dad turned around and journeyed alone over 600 miles south for the first half of May to photograph Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite. Continuously for the next three months Mom and Dad backpacked, camped, river rafted and drove thousands of miles through Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Washington and Oregon. This included three river trips: 13 days on the Colorado River through little known Glen Canyon, 26 days on the Yampa River in Utah and Wyoming inside Dinosaur National Monument, and five days on the Canyon of Lodore on the Green River, also in Dinosaur. By August 16, after three weeks in Wyoming in Yellowstone National Park and Grand Tetons National Park on a Sierra Club Pack Trip, Mom got a ride home with participants, but Dad continued on to Glacier National Park way up in Montana for 10 days and Olympic National Park in Washington for two more weeks. Dad did not see home until September 10.

Such a schedule makes it challenging to build much of a life at home. However, after I was born in 1965 Mom began to stay home from many of Dad’s photography trips and she planted a garden. Her gardening endeavors increased in size and scope until when I was about 10 years old, she had expanded the tenable area from one side of the house to three sides and her vegetable garden grew to approximately 15 by 20 meters.

Part of what moderated Mom and Dad’s push to achieve was a belief that life is meant for living and not just for work. My parents read Eastern philosophers such as Lao Tzu, who taught that happiness lies in being rather than doing. They read Lin Yutang, who in his large volume called The Importance of Living enlightens the reader with such chapter titles as, Human Life as a Poem, Playful Curiosity, Tea and Friendship, Enjoyment of Nature, and On Going About and Seeing Things. Many other texts of philosophy, art, culture and large picture books lined the walls of bookshelves in our mountain home.

Another book I remember seeing around the house, Living the Good Life: How to Live Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World by Helen and Scott Nearing, contained instructions on how to live an enjoyable, self-sufficient lifestyle. About two months before my mother passed on in 2002, I interviewed her about gardening for beneficial insects and wildlife for a magazines article. We also discussed a garden I planted at my own home near Pecos, New Mexico. At one point Mom excused herself from the dining table where we were talking, walked into her bedroom and came back with her own personal copy of Living the Good Life. With moistening eyes, she handed it to me and said, “This was our bible, besides, of course The Bible.”

Indeed, Living the Good Life had been the bible for the entire Back to the Land Movement that began in the 1930s and peaked in the 1950s. The Nearings left New York City and farmed on rural land first in Vermont, then Maine. After their book came out, they developed a national following of people who moved out of the cities to get away from Post War crowding, industrialism, pollution and competition. Also, for the first time in history, the human psyche confronted the possibility of mass annihilation with the invention of the atomic bomb.

Like the Nearings, the Hydes endured exposure to a wide range of rural and wild conditions and predicaments. Mom and Dad were survivors and minimalists who conserved resources, energy and money. Dad either repaired or jury-rigged water lines, oil pumps, motors, batteries, light switches and everything else in the house and vehicles.

In 1962, the same year Rachel Carson released Silent Spring, the Sierra Club first introduced color to landscape photography with the release of In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World with color photographs by Eliot Porter and quotes from Henry David Thoreau and Island In Time: The Point Reyes Peninsula by Harold Gilliam with photographs by Philip Hyde. While In Wildness was a well-planned art book, Island In Time was a rush project for which David Brower chose Dad as photographer because Brower knew Dad could quickly get enough artistically interesting, yet documentary feeling images to put together a book that not only helped raise the funds necessary to buy the land to establish Point Reyes National Seashore before the developers could subdivide it, not to mention it shared the Point Reyes story with Congress and President John F. Kennedy, who finalized the Bill making it part of the national park system.