What's beyond a competition win?

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

This issue we're talking to Paul Whiting who won the Amateur Photographer of the Year competition in 2005. We talked about his approach to photography, how he came to win the competition and what happened afterwards. We first asked Paul a couple of background questions about the start of his path toward landscape photography.

Paul: I was thinking back to where photography first started fitting into my life. In between finishing A Levels and when I was doing university I’d do summer jobs and I managed to scrabble enough money together to get some Canon SLR’s. It was obviously film then.

Tim: When was this?

Paul: Oh let me think: 1986

Tim: .. you went to university doing?

Paul: I went to university in 1984. I went out in Essex, I was an Essex boy then, grew up in the Midlands actually, ended up in Colchester. Don’t know if you know that part of the world?

Tim: I do yes.

Paul: Yeah, interesting place - I’ve never been back. I did meet my wife there, so there was one good thing that came out of it.

I’d gotten enough pocket money together to go and get things like ... I think my first one was probably a Canon T70 or a T90 maybe. I bought it, was really delighted with it and then it broke - I took it back to Comet where I bought it from and they said “Yeah we’ll fix that for you” and called them up a week later and said “How’s it going?” “Yeah, yeah”, two weeks later, “Yeah”, three weeks later “Yeah, yeah, no problem we’ll sort it”. About a month later I went in and said “You know this camera, have you still got it?” And they went “Well actually the technician has run off with it, so we haven’t got it!”

And they said “Look, okay have your money back”, and I went down the road to a camera shop and bought an EOS 620. So that was my run around SLR. I wasn’t really doing landscape as such then, I was just generally interested in wondering around and capturing things that interested me.

Tim: Why did you pick up a camera in the first place?

Paul: Do you know looking back, I don’t even know. I mean I’d bumble along and go through phases not even really bothering to do photography that much and the sort of the epiphany moment where I really got hooked on landscape came quite a bit later.

I’d picked up a photography mag and I’d seen an advert for a Charlie Waite talk up in London and I went my wife for the day. It was probably ’95/’96 and was in one of the exhibition halls in London.

Charlie had got a Hasselblad and medium format projector and he was starting to show some of his slides and I was just absolutely blown away!

He’d got some of the iconic stuff out of his "Making of landscape photographs", Buttermere and stuff and I was just hooked then.

And so I persuaded my wife that it would be a good idea to a get Blad as well, one with an 80mm and a 150mm and I just started trying to think about what I’d seen, because I hadn’t seen landscape photography like that then.

This is just to give you a feel for where it started for me, maybe later I’d go through a ‘Joe’ phase, but now if I look at who I would aspire to or how I’d like to think I’d try and approach photography, it is probably David Ward.

But going back to the Blad times, I’d started to go on like photography courses with Light and Land in the lakes with Sue and Charlie

Tim: That must have been one of the first courses?

Paul: Yeah it was probably maybe, so I reckon I went to the lakes in maybe ’97.

We had some decent weather, it was really good, shot some stuff and then I did the Peaks with Jo Cornish. It was a weekend course in Buxton, we didn’t get out at all, just sat in the B&B for two days while it pee'd down outside. Well that can happen on a workshop can’t it? People don’t realise that, you go on those workshops and you think yeah "I’m definitely going to get great conditions and make all these great images" but sometimes it doesn't happen.

But then even looking back on a workshop like that it makes you appreciate just the benefit of just talking to people like Joe you know and learning and discussing with other people.

Tim: I imagine you possibly learned more because of that

Paul: Yeah in some ways yeah, ‘cause it was a great opportunity for the basics, just get a pack of filters out and think about what we’re doing, what we might do in certain scenarios and stuff, whereas you know on a 10 to 15 participant course, the reality is you know you’re not going to get that much time to talk about the theory and really have discussions about it out in the field. It just doesn’t happen.

And the thing about a workshop like a Light and Land one, where’s there’s quite a few people, there’s a spectrum of abilities and experience and naturally the leaders will gravitate to those that are more at the beginner stage and if you are an absolute beginner, you will tend to use their bandwidth more and they’ll gravitate towards you.

So the Joe Cornish course was good and then I went to Tuscany with Charlie in 2000. I went to Andalucía with him the year after and I think I went to Provence with David in 2003.

Magazines like Outdoor Photography were just starting, with Keith Wilson and people like that, and after being away with Charlie, you would come back and you’d get some of the slides and he'd go “Ooh you know Keith would like that, send that off", you know it might be a picture of the Alhambra or, you know, a nice picture of something in Tuscany.

So I started to get published a little bit then and in those days they used to have this portfolio feature. It was really good then ‘cause if you got picture of the month, you’d win a £400, £500 Gitzo tripod.

Whereas these days the whole nature of the business is if a magazine is doing anything like that, you might win a little memory card worth about £30. But that’s just how the economics of landscape has shifted in the whole publishing industry. It’s not as good as it was.

Tim: Internet consumption has affected that as well hasn't it

Paul: Yeah exactly... So probably in about 2002, I entered a competition in Amateur Photographer and won ... it was one where Charlie was judging and I actually won one of his old Blads.

So there was a nice period there from about probably 2002, where between just the general publication stuff and winning competitions on a fairly regular basis meant I was starting to clean up, but I’ll talk in a minute about what, where that goes wrong a little bit. But yes so I won Charlie’s camera and that really started quite a decent profile relationship with Amateur Photographer, so they would then follow up on you six months later and say “Oh how’s the winner of Charlie’s camera doing then?” And then this Bob Elliot would come down and say “Well give us aport folio picture” and they'll say “Well what you doing then? Oh okay, have you got a digital SLR now?” “Yeah, yeah”, “Well tell us about that” and he’ll try to then construct some interesting story about how you’re shifting away from film to digital.

So my first foray into digital was a Nikon D100 I think, so we must be talking about late 2003 now, very early 2004 at a push. Six megapixels, £1,500 body, pretty awful to be honest, looking back now, but it’s your first dabble with this new technology. I was still shooting with the Blad at the time because I certainly wasn’t convinced by what the D100 was doing. Then not that long afterwards, Nikon brought a D70 out, which was about £1,000 and it was still only six megapixels. But I think it moved things on a bit, such that the images were quite useable now, you could do a lot more with it and I was just starting to shift my usage profile a bit more away from film and into digital. I’d got to the point where I’d gone to the Hebrides with David Ward and started to shoot a bit of digital over there alongside the Blad.

Once you’d started to see the convenience of digital, you then started to think "Oh hang on a minute..." I'd invested in maybe a Nikon 9000 scanner for the medium format stuff and that was £2,000 then, which was a fair amount of money and you were starting to compare the files. The cleanliness of the digital files was astonishing. I’d probably moved on maybe to a Canon 20D or something by now, so we’re talking, we’re into 2005 and I’m starting to look at the files and thinking if we ignore how big you can blow them up for a minute, in terms of quality, medium format is struggling a bit as a ... you know when you’ve scanned it with a box that costs £2,000, compared to just looking at the file at the camera, I’m starting to struggle a little bit now to see why I was using the film. If you wanted to print A3 print then the digital files are in trouble but for everything else.

So then in 2005 I won Amateur Photographer magazine’s Amateur Photograph of the Year, so that got me £5,000 worth of kit to play with.

To cut a long story short, they wouldn’t let me take a 1Ds Mark 2 as the prize because I think they were still more than £5,000 so I bought two 5D bodies and immediately sold them and bought a 1Ds2. As soon as I saw those files I was thinking I’m into this world now where I’ve got this choice to basically go and load the film up, go through all the cleaning process and expense of sending stuff off, compared to the digital, it’s just not there for me now.

I’d got enough pocket money that year from shooting a couple of weddings, winning a few more competitions, won that APOY thing, I also won Digital Photographer of the Year, won a bunch of SLR’s in the monthly competition, so I’d just got all this stuff to flog, which I did and ended up with a 1DS3.

I remember typing into the credit card machine, £5,600, in London Camera Exchange.

There’s part of me today that would still love to learn to use a large format camera, but what I’ve found in my life today is I just have so little time to get out and make images.

If you look at what we do, where I was last night, standing there agonising about what to start shooting. If I added the whole five four thing on top of that I wouldn't do anything

If I had a lot of time in the field it would be a nice challenge but ...

Tim: You end up like me doing a hell of a lot of scanning and developing, but no photographs.

Paul: Yeah well that’s the thing you see, so I’ve got into this comfortable little world with my photography now where I accept I can’t do it as much as I want. I’ve got the D800 that produces amazing images compared to where digital started, and if you treat it carefully I could make an A2, maybe an A1 print, more than I could put in my house in terms of wall space and things - I wouldn’t want anymore to be honest.

Tim: Just going back a little bit. You're shooting landscapes at this time and have got into photography, what was the primary driver for that? Was that because you loved being outdoors?

Paul: Yeah I think definitely ... it all sounds a bit corny doesn’t it, about why a landscaper photographer starts. The primary driver is it’s a reason to go out there and I could go out there now to be honest, a bit like we did yesterday and reach the end of the day and say well I didn’t make any great images but do you know what, it was just lovely to be out.

Compared to doing you know the mundane routine of life, I’ve lived in urban areas all my life, and then to just take a few days away and get out to the coast or the woodland, it’s just a lovely experience.

Tim: And that was the driver at the time then?

Paul: It was yeah.

Tim: A bit of a revelation seeing Charlie’s images then?

Paul: His work was and still is poles apart from David in terms of approach and result. Joe is somewhere in the middle of the two of them in terms of what they want to achieve at the end, but still for me Charlie was the trigger to think actually "you know I can make some images that are on a different level from my stock shots, my postcard stuff" and then of course I got to meet David and started to see in a little bit more abstract way.

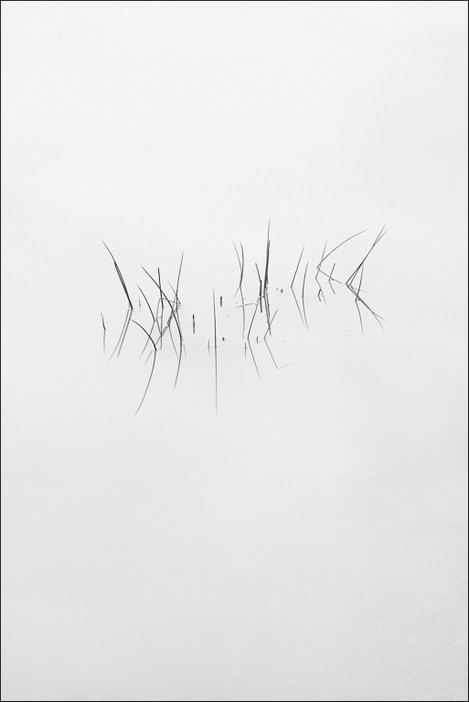

I still can’t come within a million miles of seeing things in the abstract way he does, but it’s just that focus on trying to look at details, trying to look at the underlying structure in things and make something that’s more visually challenging than just a straight record image.

Tim: So in terms of entering competitions, what made you start entering them in the first place?

Paul: I think this is part of the problem I’ve got with my photography. The upside of the competitions is that there’s an element of challenge, there’s an element of wanting to win.

There's something nice about getting shortlisted and published. After a time being regularly published, it became a bit run of the mill, but when you first start, It's great. I remember the first picture I had in Outdoor Photography of some nice trees in Tuscany, it was like "wow", you know, I can go and show my family and friends!

But ultimately what I look back now and realise, and to some extent a little bit miss its absence, is it gives you a goal and structure to work around.

I know David was, and to some extent I am still a bit anti competitions. There’s an argument that says it actually produces a convergence of styles; You’re shooting for somebody else ultimately and you then get wrapped up in this very difficult world of trying to imagine what these anonymous judges might want.

The problem is if you go out and shoot for a theme deliberately, you are then faced with all those problems of "what do they want?" and you try to conceive an image in your mind, go and make it and then you’re thinking "will that one win?" you know, "what will everybody else do?" and it’s a stupid, pointless exercise, because you don’t know what anybody else will do, you don’t know what anybody else will submit and I think as I look back, I did it because I was successful and, if you like, it sort of fed the profile desire. It gave a very strong structure.

You know if you want to win an annual competition that requires 10 themes, you’ve got a lot of structure and purpose laid out in front of you in that sense, but on the other hand you can feel quite dissatisfied ‘cause you think there was the architecture theme that I spent two months trying to deal with or the ones that always used to kill me, ‘cause I’m absolutely hopeless at it, would be the people ones - portraiture of any description and then you look back and you think why did I do that? Well actually you should be out photographing trees, coasts, mountains and rivers and doing things that you love doing.

Tim: Would you consider yourself as quite goal oriented?

Paul: Yes, yeah I think so. I mean I did a degree in maths and a PhD in theoretical physics so I’m on the sort of classic spectrum of autism if you like, I’m very much down there, my brain works around numbers. I’m a classic sort of male engineer I suppose if ever there is such a thing.

So that goal and the difficulty then to some extent and this is where I’ve been for the last two or three years is really asking the question why go out and make images? What am I going to achieve now that I haven’t already? I’ve more or less done the competition and coverage thing really. I’ve been published, the internet has now taken over, so all of the printed publications I used to get published in have gone and they’ve been superseded by social media.

Tim: Yep, yeah. I imagine the equivalent is a chase for likes and favourites

Paul: Yeah exactly, so yeah and nice captures and awesome image on Flickr and things like that, you know and that’s a whole different topic in itself isn’t it?

So I think for me I’m struggling in that world a little bit now "what is the goal? What is the motivation for doing it? I had a bit of a quick Facebook conversation with David Ward about it the other day and he just said and I thought it was a really good point, he just said “Whenever I shoot” and I genuinely do believe this for him, he said “I’d never ever consider an audience. I just shoot for the selfish pleasure of shooting” and to some extent in a way there if you think of what David is making a living out of photography with, it’s primarily around selling the service and the service is trying to teach other people his philosophy through showing images he likes and you either like it or you don’t and clearly a lot of us do, ‘cause he’s got a big following.

Whereas if you take someone like David Noton, someone who is a very, very competent photographer, but I would argue that ultimately his main drive when he picks a camera up is to work out where he could sell or place the image, ‘cause that’s been his photographic life.

I guess I'm trying to get back to how I was in 1997 or 1998 in a way, when I first got into it through liking Charlie’s images, of saying there is no other reason to do it but to enjoy it, but it’s quite hard to do for me...

Tim: The pleasure of getting it back again.

Paul: Dave Tolcher and I were saying yesterday that there’s still this small element in you that wants recognition from others; that you know your image is good or you want some feedback one way or the other on what you’re doing.

I was wrestling in my mind with, over the whole motivation thing really has been so deep in the last couple of years that 12 months ago I was very close to just chucking all of the kit away and saying you know it’s got to the point now where it’s become a hobby you spend so much time thinking about it, reading about it and worrying about whether you’re going, whether what you’re doing is right, wrong or indifferent, but proportionally so little time actually executing it, it’s become a negative force in my life if that makes sense. But I’ve sort of pulled back from that really and have carried on.

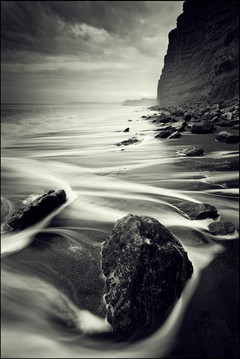

I think to some there can be a bit of a spiral going on there where you don’t get out for whatever reason or perhaps you tell yourself you know you’re not going to go out. I mean up in the Lakes last week I did my first stupid o’clock dawn shoot for a long, long time. I finally did it on the last morning before we were driving home, it was a 3.30 start at Buttermere, so alarm clock went off and I was round the lake at 4.15 and I was really, glad I did it, but it was such a physical and mental effort to get out of bed that early. I just hadn't done it for so long.

Whereas if I look back to when I just did it for the fun, I just didn’t care then. I think to some extent it is quite a selfish pursuit, landscape photography, either as a professional or an amateur and sometimes you think about how this impacts the family, you know, that I’m going to possibly set an alarm and wake everybody at three thirty on holiday and it’s like my wife said to me, she said “You’re just over-thinking it”. She was as simple as that and in a way it sometimes takes a dispassionate view from somebody that’s not really involved in it that much, but watches what you’re doing and how you’re behaving to give you a bit of a kick and then you can go "yeah, actually it’s just a damn hobby" and just go and enjoy it.

Tim: Yeah. So what bit do you actually enjoy most now?

Paul: I suppose I'm just trying to make something a little bit different or a little bit more challenging. It’s that challenge of, rather than turn up somewhere and just do the obvious shot, trying to make something a little bit different and in that sense I don’t care.

I know full well that if I post probably what I would consider one of my best images on Flickr, I’ll get hardly any interest in it, because it might be just a long shot of some branches of a tree or some leaves or something, whereas most you know 99% of the people on Flickr, they want a foreground and a middle ground and a big fantastic sky and stuff like that.

I’ll do that too if it’s there probably, you know because you just, sometimes if it’s a fantastic light and a great scene in front of you, you just fill your boots! But ultimately you sort of get to feel "Well anybody could do that". Anybody who is a competent camera operator could probably turn up and do it.

Tim: Yeah, it’s a very good phrase that, camera operator. There is a certain truth to that. That is enough for a lot of people though.

Paul: Yeah exactly and ‘cause there’s an element of just recording, people use that word ‘capture’ don’t they?

Tim: Yeah.

Paul: On Flickr and the social media, "great capture", but it’s like rather than you’re engaged in the process of image making it reminds me of a gamekeeper out in Kenya, shooting a lion and loading it on the back of a truck and saying “Right that’s one more down”.

Tim: It’s out there and you haven’t done anything, you just happened to have found it.

Paul: You know 10 years ago I would have been quite happy just to turn up and shoot that ship at Saltwick, the classic Joe shot and just say "well I’ve got that in my collection now" - and why shouldn’t you have!? You know you were there, why would you turn down the opportunity to shoot the ship? It’s actually because generally I’d always look back when I looked at it in the future and go yeah but all I’ve done is copy Joe’s image or somebody else’s interpretation of it, do you know what I mean? I think it’s that and that’s why I like David’s philosophy so much, trying to steer away from the icon if you can and go to somewhere that’s got some interesting possibilities, but where you can effectively make an image that’s unique to you.

And actually you know you’re not copying anybody else and it’s unlikely anybody’s going to copy you.

Tim: It’s like we were saying last night about going to places with strong icons like that, they can be a distraction almost because they are such strong elements of subject matter that you’re inevitably drawn to them.

Paul: Yeah you almost feel obliged, you know how could I have gone to Saltwick last night and not shot the Nab and the wreck ... because you know let’s face it as though as well known as it is probably in photographic circles, the wreck of that ship lying in a bowl of rocks is still quite unique.

You’re just totally drawn into these really interesting things, because you know, let’s face it down in Winchester there’s no wrecked ship like that right? So there’s that element where you know it’s novel to you and then there’s the element of well I really ought to make an image of this.

We stood together and tried didn’t we to do something a little, a little bit different or at least tell ourself we were going to avoid the big thing, but I spent an hour probably when I first arrived last night, fighting that, fighting and fighting and fighting about I must go and photograph the Nab and I must go and photograph the reflection. But ultimately you know I couldn’t, I couldn’t ever see a point where I’d completely give it up, because I’m still drawn to it really.

I suppose the interesting question you’re trying to really get me to answer is well exactly what are you drawn to then and what’s stops you just sort of sticking it all on Ebay finally and not doing it anymore?

I think it’s that ... one thing I like about photography in a way and sometimes it’s again this double edge sword thing, but it’s knowing that no matter what we did last night, whether we succeeded or failed and you know let’s take the case where we didn’t do as well as we’d liked, is you know when you wake up tomorrow there’s always another chance or they’ll be somewhere else to go and try again. Because the bottom line is if we go and take a stunning image today of a tree trunk in a field or wherever it is, you know that could then completely obliterate in my mind the fact that you know I should have done better at Saltwick last night and that’s the thing is, you know you have quite an intense feeling to some extent about how successful or not last night’s shoot was, but once you get into other things, it quickly fades.

Tim: I mean I suppose the other thing is if you didn’t have the camera with you, would you have spent the whole of the evening standing around enjoying the view and company

Tim: I mean I suppose the other thing is if you didn’t have the camera with you, would you have spent the whole of the evening standing around enjoying the view and company

Paul: No I wouldn’t, there’s no two ways about it, you wouldn’t have that bond with the location, ‘cause if you turned up with your family you might go down to the beach and you’d take them over there and you’d go “Well there’s this nab and there’s a bit of the history behind it and look at this ship here” and you’d walk along and everybody would go after about 15 minutes “Well okay so, but you know let’s walk back to the car now and go onto the next location”.

Tim: But I found it fascinating just standing there and watching the light last night and taking it all in, looking at the reflections

Paul: But because I don’t go out often enough I think these days, I don’t find so much that the technical part of photography suffers that much. I can quickly get back into operating the camera, but I think where you do suffer when you don’t go out enough, is your brain just takes longer to switch back into seeing and thinking about and anticipating to some extent all of the things that you can and could make.

I guess that’s the advantage isn’t it of being a large format photographer to some extent, is you know because it’s a slower process, because it’s a more expensive process to get the image back and you won’t just snap away.

Tim: You do spend more time looking I think (maybe too much)

Paul: Ultimately I think that that’s the advantage if you like that large format photographers still have over SLR users.

When you approach a new location I watched Dave Tolcher and myself go to this place yesterday and Dave’s approach, because he knows ultimately he’s got a make a decision to pull a trigger and lose a sheet of film and process it, he’ll walk round first and try and decide which is the best thing that ultimately he’ll end up with in the time he’s got. Whereas when you’ve got the SLR and you know that actually all you’re creating is a file that you can throw away for nothing if the needs be, what I think I did yesterday in a way compared to Dave was, I would just almost go round scooping up possibilities, rather than actually assessing possibilities first and then coming back and saying okay, this is the very best one.

Tim: I can understand that completely. The thing about icons I’ve always thought is it’s about time investment. The time you spend taking a picture of the icon or the default shot, waiting for the light etc, is time you aren’t spending looking for other pictures. That's a choice really and one each photographer has to make

Paul: Yeah, but in a way I think that David refers to it a similar issue example in his second book doesn’t he, where he sees some competent images from one of the participants and says “Why do you do that?” And the guy, eventually he gets the guy to admit that there’s this fear of not making an image.

Tim: Yes, yeah. Fear plays a huge part in it doesn’t it?

Paul: Yeah and in a way I sort of don’t have that anymore really, partly because as I said, you know I can turn around and say there will be another opportunity. I might never, ever come back to Saltwick again, but I’ll have learned something, even subconsciously from last night and the big learning there to some extent was watching, I was absolutely convinced there was no cloud of any interest that sun was going to drop into but there wasn’t, so in a way there part of the lesson was you know and I’ll remember it next time, is just don’t bank on what’s going to happen in the next half an hour, take something

Tim: Which is where large format has it's weakness again though?

Paul: Yeah and I didn’t, I spent too much time faffing, but yeah so there will always be another opportunity I think and so it wouldn’t have bothered me if I’d taken nothing ultimately.

Tim: In terms of winning the Amateur Photographer of the Year, how was that and how did that effect your photography at the time? Did it open doors for you for making some money out of it or did you think about going professional or anything like that?

Paul: You can always look back and say "well I should have done this or I should have done that", but if you think of 2005, 2006, we were about a year or so away from the recession kicking in, so I’d actually got what I felt at the time was a reasonable little pocket money source where the hobby was becoming self funding really and I didn’t know that was going to dry up in the way it did and the way it did dry up actually was that your sort of Frosts and Notons and a lot of your pros that had always relied on books and stock, actually that was drying up for them and so they were switching, they themselves were switching back to education, so you’d find that rather than coming to what ultimately was a freelancer like myself then, they’d go back to a pro to get images and written content, whereas before the pros wouldn’t be interested in writing you know a five page article for Amateur Photographer.

Now they were thinking "oh actually now I’ll take a bit of money from that", ‘cause what they do is they probably sign them up on a 12 month agreement to go and write an article a month or something. So my work sort of dried up. So it never really opened any doors. I suppose the frustration was in my mind a door was starting to open where some income was coming in and it closed again quite quickly really, because of what happened, the way the market changed, the way publishing changed.

Tim: So you’re quite lucky in a way because it you could have made a risky decision on the back of winning and then the recession could have happened.

Paul: Yeah - and the thing is you know I look ... we were talking yesterday in the car again about coming up, but how do you, you know just purely from selling images now, it’s impossible to put food on the table really. There’s no money in it. Most people I know who are full time professional photographers or in the industry, nearly all of them that I can think of, they’ve got a whole blend of income streams now, whether it be you know offering services like a lot of the things that you do, you know or going out running workshops, writing books. There isn't such a thing as a 'pure' landscape photographer. So that’s not something that I agonise over anymore to be honest, because we’d have had to make such a dramatic lifestyle change with my kids and work.

Tim: How old are the kids?

Paul: Kids are 15 and 12, so you know I’ve still got mouths to feed there for a few years yet.

Tim: So where’s the photography going to go now? That’s a question for you?

Paul: Well I think I’m going to try and just hold that kick up the backside from my wife really, which is you’re over-analysing, just go and enjoy it.

So I think for me what my plan now is to just try and do a few more trips like this, try and make more of an effort to go out at the weekends, ‘cause again you know once you get into that downward spiral thing of I haven’t got time to do it, then it’s very easy when push comes to shove, just to make sure that there is no time to do it. There’s always something else.

Whereas it isn't that difficult to agree with my wife to set aside one weekend every month and go on a couple of hundred miles each way trip if I wanted to. You know so I could go to Cornwall, encourage people like Dave and friends and yourself to just meet up more regularly and do this stuff really, ‘cause I mean the blokes are notoriously hopeless at doing stuff like this.

I think you know my challenge is to just get out with the camera more, go out more and care less, care a lot less about what anybody else thinks about it and just go and enjoy it for what it is really, which is just a nice way of getting out into the fresh air.

Tim: Well thank you very much for the interview!

Paul: My pleasure!