First in a series of articles by David looking at Creativity.

David Ward

T-shirt winning landscape photographer, one time carpenter, full-time workshop leader and occasional author who does all his own decorating.

Part 1: Four Stages…

During my recent webinar for On Landscape I was struck by the fact that one question kept coming up in a number of different guises: how do I go about finding an image? It was apparent that most people felt I had some trick that I employed when searching for an image. In this article, the first of two parts, I’m going to endeavour to explain how I feel the creative process works for all of us. This recaps some of the ideas that I discussed in Landscape Beyond but expands them to include what I consider to be perhaps the most important single aspect of being in a creative frame of mind.

The capacity for creative thought, and the ability to subsequently act upon on it, is inherent in all of us - though often neglected or suppressed. Over the years I have met many people who have told me that they’re not “at all” creative. I fundamentally disagree with this point of view. It seems to me that this opinion arises from a narrow and often mistaken idea of what creativity is. The mystique that surrounds the notion of an “Artist” in Western society is undoubtedly partly to blame. Creativity has traditionally been seen as the domain of gifted, intuitive, often eccentric individuals with turbulent lives – Vincent Van Gogh is perhaps the archetypal artist. These individuals are mythologised and set apart from ordinary folk. It may be a cynical thought but it does the sale price of their work no harm for them to be considered slightly deranged demigods. Whilst it is true that some artists fit this otherworldly stereotype the majority do not. Psychologists have long characterised creativity as originating in the right hemisphere of our brains. The two hemispheres are thought to be responsible for opposing forms of perception and behaviour:

Left Brain Right Brain

Analytical Synthesizing

Logical Random

Rational Holistic

Sequential Intuitive

Objective Subjective

Concerned with detail Concerned with wholes

Recent studies using functional MRI scans have shown that this notion of a strict split between hemispheres isn’t correct. The actual picture of activity is more subtle and complicated than the right-brain/left-brain paradigm suggests. Putting that inconvenient truth on one side, it will be obvious from a quick glance down this list that the traits we associate with creativity are all right-brain and that the traits thought necessary for operating a camera are left-brain. But ultimately, it doesn’t help us very much to say where traits might originate because, unfortunately, we seem to lack a convenient switch to turn on the appropriate behaviours.

So, let’s look a little more closely at how the creative process works. Psychologists have suggested that we can split this into four stages; preparation, incubation, illumination and verification. Let’s take them in turn.

PREPARATION

The stage when we identify an opportunity (a problem to be solved) - in our case, finding something to photograph - and collect ideas about how we might utilise the opportunity (solve the problem). The problems artists of all kinds face are said to require a divergent rather than convergent approach. Convergent thought processes are used to solve problems that have single solutions, like mathematical formulae, where we home in on the solution. In contrast, divergent thought is needed to find a solution to a problem that has many possible solutions - whenever we make a photograph there are a host of alternative ways of photographing the same subject. We need to come up with as many different ways of solving the problem as we possibly can in order to guarantee an original solution. It is therefore vital that we don’t deny ourselves opportunities by blindly following a plan to make a predetermined image. We should remember that whilst experience teaches us what does not work it doesn’t teach us what will work until we’ve tried it. This requires us to have confidence in our own abilities, something we gain through practise and experimentation. Every time we press the shutter we need to make a leap of faith as well as a leap of the imagination.

Typically for landscape photographers, the preparation stage would be spent in the field – though not necessarily so as we may already have thought of a subject but be struggling with how to tackle it. At this stage we need to be fluent and flexible in our generation of ideas and resist the temptation for closure – we need to keep our fingers off the shutter release as long as possible. Artists from different media have described this frame of mind as a strange mixture of insight and naiveté – a need always to look at our surroundings, no matter how familiar they may be, as if for the first time. The British photographer Bill Brandt said that:

Most of us look at a thing and believe we have seen it, yet what we see is often only what our prejudices tell us to expect to see, or what our past experience tells us should be seen, or what our desire wants to see. Very rarely are we able to free our minds of thoughts and emotions, and just see for the simple pleasure of seeing. And so long as we fail to do this, so long will the essence of things be hidden from us.

And Vincent Van Gogh wrote that 'A feeling for things in themselves is much more important than a sense of the pictorial.' But sadly, most “How to Make Great Photographs” discussions concentrate on the pictorial. It’s the easiest topic to write about but it’s also, in many ways, the least important.

How might we achieve this insightful state of mind? As I’ve already noted, we need to be receptive and open to possibilities, but this alone is not enough. We also need to shut out the everyday babble of thoughts unrelated to the task at hand; we need, in short, to become detached from anything not directly linked to making the image.

I wonder if any of you share this common scenario from my experiences as a landscape photographer? I find myself returning to full awareness, one knee sodden from immersion in a cold and muddy puddle, having crouched atop a hill in the wind and rain for an hour and a half making a single image. I become so lost in making a photograph that I’m almost in a trance like state, oblivious to everything but the task in hand for extended periods of time. In this intensely focused state, physical discomforts are irrelevant to me; my mind is lost in a place where the physical no longer matters. In this dream space, I’m unaware of the passage of clock time - that mechanical manifestation of universal time - because I’ve become totally immersed in subjective time. This is a plastic realm where seconds can stretch into hours and, conversely, hours can be compressed into an invisibly small interval. It’s also a realm where we care nothing for the discomforts or needs of those around us. Little wonder, then, that our loved ones are often reluctant to accompany us on photographic sorties.

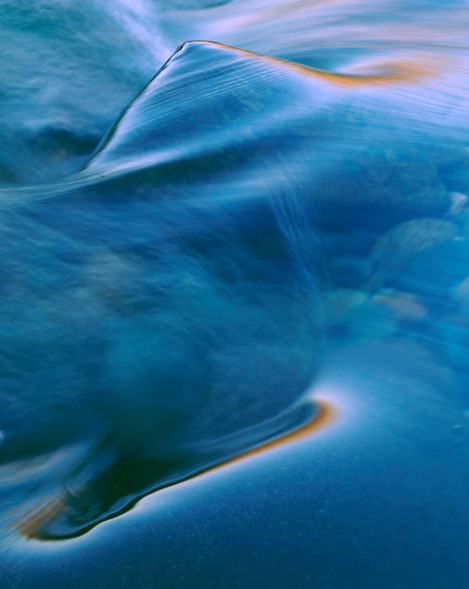

This meditative state is not a mystical condition but a behaviour, widely recognised by psychologists, known as flow state. The Hungarian born psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi (Read Guy Tal's article Art and Flow in Photography for more on this) was the first to identify and name the condition. The name refers to the feeling of being “lost in the flow”, carried along by the task in hand - as if caught in a powerful current on a river. The vector of your journey is seemingly determined by the demands of the undertaking and not by self-reflective thought. The phenomenon has been widely known for a long time; “in the groove”, “in the zone”, “on a roll”, “on fire”, and “in tune” are common phrases from a variety of different fields that refer to the state of consciousness ascribed to flow. No one had ever rigorously studied the phenomenon before Mihály began working on it in the late 1950’s.

Csikszentmihalyi arrived at the concept of “flow” after first noting the behaviour of some artists. He realised that if something they were working on was going well they became intensely preoccupied - sometimes to the total exclusion of bodily needs such as hunger, fatigue or physical discomfort. It is said that when Michelangelo was painting the ceiling of the Sistene Chapel he would sometimes work for several days at a time without rest. Eventually, complete exhaustion would overcome him and he would collapse. But upon waking he would return to his work as soon as possible. Essentially, he and other artists were completely lost in their work. In fact the phenomenon is not limited to artists but is experienced by athletes, surgeons and musicians as well as in many other walks of life. Anybody engaged in what Mihály referred to as “an intrinsically rewarding experience” may experience flow.

Csikszentmihalyi wanted to understand the conditions of this state and how it arose. He and his collaborators began a very widespread research program, interviewing people from all over the globe and from many different professions to try and find the roots of “flow”. Eventually, he proposed six factors that characterise this heightened state. I have listed them here with some examples of how they might relate to making a photograph.

- An intense and focused concentration on the present moment, e.g. bringing all our skills to bear at maximum intensity on making an image.

- A merging of action and awareness, e.g. a feeling of brilliant clarity in which the craft associated with making a photo becomes seamlessly blended with one’s compositional choices.

- A loss of reflective self-consciousness, e.g. we become unaware of ourselves and our surroundings; everything extraneous to the making of the image becomes completely irrelevant – this includes “loved” ones!

- A sense that one is in control of the situation or activity, e.g. a sense of quiet assurance that we’re making the right technical and artistic decisions.

- A distortion of temporal experience, e.g. an hour’s effort might be compressed into a subjective span of a few minutes or might even seem to have taken no time at all.

- The experience of the activity as intrinsically rewarding (also referred to as autotelic experience), e.g. the “buzz” we feel when an image has matched or exceeded our expectations.

Being in the flow isn’t, however, akin to being a mindless automaton. Flow is an innately positive experience; it is known to "produce intense feelings of enjoyment", sometimes even “rapture”.To a spectator, one might appear to be lost from the present and unheeding but that’s not how it is experienced. Indeed, it can be argued that we are never more intensely “here” than when we are in the flow. Mihály Csikszentmihalyi has shown that the time spent in flow makes our lives more happy and successful. He and his fellow researchers believe that flow experiences lead to positive feelings about ourselves, in the same way as meditation. Perhaps more importantly for us, as photographers, flow also results in better performance. The joy that we experience in the flow means that we crave further experiences. But pursuing something that invokes flow is not just searching for a temporary “high”. Research has shown that repeated flow experiences permanently increase our overall levels of happiness.

There are three conditions for achieving flow:

- The activity must have a clear goal, e.g. solving the puzzle of composition and making a personally satisfying photograph.

- The task must have clear and immediate feedback, e.g. success or failure is readily apparent and we have the sense that technical (or aesthetic puzzles) are being satisfactorily resolved.

- There must be a balance between one’s perceived skills and the difficulty of the task, e.g. one doesn’t feel totally out of one’s depth!

The last condition means that novices - whose skill levels are necessarily low - are unlikely to achieve flow. There is always a balancing act between the challenge level and the skill level. If the challenge is too tricky it is improbable that we will achieve flow. And similarly, if our skill level far exceeds the challenge flow won’t happen.

I mentioned earlier that flow leads to better performance. This is one of its long-term benefits. Because we need to match the challenge of any task to our skill level in order to enter flow we develop a habit of looking for new challenges. Hand in hand with this goes the further development our skills. So meeting a challenge gives birth to higher skills which in turn encourages us to look for bigger challenges… and so on. Flow, therefore, fosters our personal development and Csikszentmihalyi has stated that happiness is derived from continued personal development.

In my experience, the greatest difficulty is getting oneself into the flow. I’ll look at how I do this in the next issue. But first, let’s look at the other three stages of the creative process.

INCUBATION

When problems arise in our everyday lives we often follow the age-old advice of ‘putting it on the backburner for a while or even ‘sleeping on it’ until the solution occurs to us. This is a way of letting our subconscious work at a synthesis of the different elements of the problem and so arrive at a conclusion. We’ve probably all had the experience of going out to make images but being unable to find any satisfactory compositions, yet we might return to the same location in similar light and see pictures all around us. In the intervening time, we will have incubated ideas about how to approach the subject from our original visit. This is why we often find it difficult to make images in a new environment; we have to spend time assimilating many different complex factors and ideas before we are ready to progress to making images. If you are stuck for a solution leave the problem to stew rather than worrying at it like a terrier with a bone. When you return to it ideas will flow more freely.

ILLUMINATION

This is the sudden realisation of a solution to the problem, how to make the photograph in our case. History is littered with anecdotes about such moments from other arenas of creative thought: from Archimedes jumping out of his bath and crying ‘Eureka!’; to the moment when Isaac Newton watched an apple fall and understood the notion of gravity; to Darwin extrapolating the theory of evolution from his study of finches in the Galapagos Islands. It is this seemingly unexpected insight that bolsters the myth of a kind of divine genius granted to only a few individuals. But this is just part of a process; neither Archimedes nor Newton nor Darwin arrived at their particular moment of insight out of the blue. They all worked on the problems for a considerable length of time, from months to decades. In fact, in the case of the last two revelations, there is strong evidence to suggest that these particular moments are retrospectively applied myths that never actually happened. We all have little eureka moments every day; we use this process when doing mundane tasks like trying to remember somebody’s name or solve a crossword. “Aha!” we say to ourselves, often not realising that we have emulated such august individuals indeed, if not in scale.

When making a photograph we’re trying to solve a multi-dimensional puzzle. We obviously have to work out how best to flatten a three dimensional space into two dimensions. We also have to work out how best to incorporate time in the image; do we freeze motion or allow it to become blurred (and if so, to what degree). Perhaps less obviously we are also trying to work out how to balance the colour dimension. This is a complex task in itself. Put all of these five dimensions together and you have an incredibly complicated puzzle to solve. We might not shout “Eureka!” but I think we should recognize more often how commonplace but amazing this creative problem solving capability is.

VERIFICATION

The final stage is when we reality test our solution by implementing it and making an image. Obviously, the solutions won’t all be masterpieces but the longer we can delay closure the better the chance. If a particular photograph, a single verification, fails to meet our criteria then we must simply start again from square one. One great advantage of digital photography is that the verification is instantly available for the photographer to assess without the traditionalists agonised wait of hours or days. The first four images below were all made on a single afternoon in Death Valley, California. The first three were made on a compact digital camera. The series represents the development process that I have described here, leading to my particular answer to the divergent problem that these subjects posed. As can be seen, I made of images that offered solutions to the particular compositional conundrum posed by this abandoned car.

The final image of the rear window of a wrecked car that was taken on a 5X4 camera using Velvia and is the one I feel best answers the question posed by the subject… on that day.

But on a different day, two years later I reached a different solution.

The hardest part of the process is the delaying of closure because evolution has programmed us to quickly seek the simplest solution to perceptual problems. The overriding visual assumption we make when we look around us is that our environment is not inherently deceptive. To get past this we have to trick ourselves in to seeing things in a literally ‘new light’. One way of doing this is simply to study your subject for a long time until it no longer seems familiar so that new relationships and patterns arise in the subject (try staring at any word for long enough and you will see that it suddenly becomes disconnected from its meaning, the ordering of the letters becomes strange and unfamiliar). The photographer Duane Michaels declared that "I do not believe in the visible. I do not believe in the ultimate reality of automobiles or elevators or the other transient phenomena that constitute the things of our lives... Most photographers believe and accept what their eyes tell them, and the eyes know nothing. The problem is to stop believing what we all believe." Our perception is programmed to look for patterns and to switch off when a plausible solution has been found. For photographers to see something afresh and for this to excite the viewer, the trick is to go beyond the obvious and to embrace the ambiguous. Look hard, think long and only then press the shutter release.

The obvious conclusion to be reached from analyzing the creative process is that there is no single correct approach to making an outstanding photograph. In fact, by definition, an outstanding image will have arrived at a unique and personal solution to the divergent problem that the subject had posed the photographer. For this reason, Edward Weston wrote that “…to consult the rules of composition before making a picture is a little like consulting the law of gravitation before going for a walk. Such rules and laws are deduced from the accomplished fact; they are the products of reflection”

Next time… In the next issue I will look at how I prepare to make an image and explore some ways in which you can get in the flow.

Read part 2, Getting in the Flow.