Master photographer

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

Harry Callahan, born 1912, was a photographer many of us could relate to. He wasn’t a graduate of any particular art school or a rich family who could support a creative life. Harry, an engineer by training, worked for Chrysler during the Great Depression and only started photography as a hobby during a ‘mid life crisis’ in 1938 (sounds like an early life crisis to me). He was going to buy a movie camera but couldn’t afford one so was convinced to buy a twin lens rolleicord instead. He joined a camera club shortly after but was never really happy with the camera club ethos and moved to another very soon where he at least found someone he could relate to. The big ‘epiphanic’ moment (I’ll get that word in the dictionary one day) was when Ansel Adams came to talk at the club in 1941.

Meeting a photographer that lived and breathed his passion had a profound impact on him. Interestingly, Ansel Adams showed one of his only ever series of photographs, a set of pictures of the surf at the San Mateo County Coast; pictures that were themselves inspired by Steiglitz’s ‘Equivalents’ cloud series. This set Harry on a journey of ‘seriality’ where he looked for inspiration in the photographing of things rather than the things themselves. He had already had dissapointments making visits to beautiful locations and producing little that motivated him.

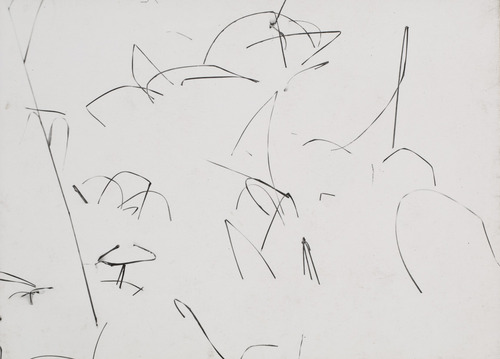

A couple of years later he produced a series of pictures “Weeds in Snow” which set the foundation for all of his future work (which you can see alongside this article), even though it wasn’t published until 1946. This probably coincided with his recruitment to the Institute of Design, Lazlo Moholy Nagy’s Bauhaus “New Vision” college. This recruitment was timely as the previous years were depressing for Harry - trying to fit photography in his spare time.

The exposure to Lazlo Moholy Nagy and Steiglitz (his contemporaries within the circle of photographers at the time) exposed Harry to ‘experimental’ camera techniques such as multiple exposures, extreme contrast, etc. This, and a contrary attitude to any ‘accepted’ patters of art. His approach was both intuitive and documentary - a combination of analytical engineer and iintuitive artist.

To understand Harry Callahan’s work, you need to appreciate the seriality of photography, where the connections between photographs are as important as the photographs themselves. These aren’t necessarily projects, but are ways to distilling the essence of an idea through similarity and difference. The viewer interprets a series through comparison and this gives the photographer a great degree of expressiveness. Harry Callahan did take the occasional individual photograph (especially in street photography) but the majority are weaker when read on their own.

Later on in Harry Callahan’s life, he brought Aaron Siskind into the ID to teach and they then both moved to the Rhode Island School of Design. His work here and for the years after his retirement continued to be fresh and exciting for many at the time (and his grasses work is one of my favourites which was produced in 1988, three years before he had to stop taking photographs due to ill health and seven years before his death).

Harry Callahan didn’t think of himself directly as a landscape photographer, he sampled too much of the photographic repertoire to be called anything but simple a photographer, but his landscape abstracts and deadpan views were hugely influential in the mid to late twentieth century (He made New Topographic work decades before Baltz and Adams).