Human vision and the digital photograph

John Hardiman

An Australian bloke who enjoys making fine art prints and capturing the moods of an ever-changing landscape. He runs a small home based studio in Melbourne for fellow photographers and artists in need of prints and reproductions, among other things.

Colour management as we know it in digital photography is often more about strange terminology than anything else, presenting itself in the form of profiles, gamut’s and unusual numbers. But colour management goes deeper than that, it centres around human vision which is a fundamental part of the visual arts, including photography. So I believe a deeper understanding of human vision, and the way it interacts with colour management can help us unlock the potential in our images, as we edit, view and print.

A fundamental principle of vision is seen in the interaction of colour. Leonardo Da Vinci wrote of these effects in his notebooks 500 years ago, and his observations are just as relevant today. “Of several colours, all equally white, that will look whitest which is against the darkest background. And black will look intensest against the whitest background. And red will look most vivid against the yellowest background, and the same is the case with all colours when surrounded by their strongest contrasts.” In essence, Leonardo noted that the colour perceived is determined by its surround.

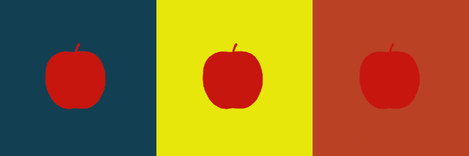

“And red will look most vivid against the yellowest background” You be the judge, the point here is the effect of different coloured backgrounds on an adjacent colour.

While these examples may seem like a pre-school lesson, I believe they provide an important insight.

The effect of a deep black can be counter intuitive. To brighten an image, it would seem more logical to increase the exposure than to lower the blacks, but a deeper black can be exactly what’s needed. In the same way, coated photographic papers with deep blacks, such as satin or baryta papers, appear to have more punch than rag or matte papers, even though the paper itself is just as bright, the blacks do the heavy lifting.

In colour science, a related effect was studied by Bartleson and Breneman. Just as contrast can be increased by using deep blacks within an image, they observed that contrast appears to reduce if the surround is dark, and increase if the surround is light, as shown here with Ansel Adam’s ‘Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico'. I came across this example during a discussion with Mark Fairchild, a Professor of Colour Science at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Mark had attended an exhibition which displayed Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico as the centrepiece of the show. Unfortunately, it was presented in a way that Adams would not have intended, against a dark background and directly illuminated. The effect created luminous whites, but the all-important black values appeared dark grey and effectively destroyed the centrepiece of the show. In his book The Print, Adams states his preference for a middle grey background. Today, official use of his images is generally not permitted on a dark background.