Charles Twist's take on photography

Charles Twist

The first serious steps on my photographic journey began 20 years ago, when I moved to sheet film and view cameras, primarily capturing full-colour landscapes. Since then, I have delved into the history and technology of my craft. Rediscovering and mastering the reversal processing of photographic paper was a pivotal moment for me, laying the foundation for a collaborative project focused on creating sepia portraits at events using vintage methods and equipment.

Subsequently, I designed and constructed my own view camera. Presently, I continue to employ the reversal process with a century-old camera to compile my personal photo-diary. Simultaneously, I use my homemade camera, fitted with a digital back, to craft colour photographs of landscapes and architecture. While I am proficient in both analog and digital technologies, my cameras all share a common feature – a bellows at their heart.

Fascination is a good place to start in my art. It comes from the Latin for a spell and quite appropriately describes the feeling of wonder which beckons me to stop and admire something beautiful or intriguing. It gets around the demand for aesthetics in artwork and legitimises the expression of diverse interests. It also has universality by summarising neatly the feelings of the artist before his subject and the public before the work of art. Of course, it is not art per se but it convinces the artist to transform his subject in to a work of art. Equally, it convinces the public to transform the created object in to a work of art too. I take the stance that art is always created afresh and that it does not exist in the absence of the human mind; some may disagree. Whatever the belief, the need for fascination remains.

Fascination is a good place to start in my art. It comes from the Latin for a spell and quite appropriately describes the feeling of wonder which beckons me to stop and admire something beautiful or intriguing. It gets around the demand for aesthetics in artwork and legitimises the expression of diverse interests. It also has universality by summarising neatly the feelings of the artist before his subject and the public before the work of art. Of course, it is not art per se but it convinces the artist to transform his subject in to a work of art. Equally, it convinces the public to transform the created object in to a work of art too. I take the stance that art is always created afresh and that it does not exist in the absence of the human mind; some may disagree. Whatever the belief, the need for fascination remains.

Landscape photographers are fascinated by a great diversity of subjects. Some are attracted to the sanctity of wilderness, others to graphic patterns, yet others to the simple pleasures of life such as a beautiful sunset. It is easy to dismiss this latter as a naïve response after having witnessed the depths of thought associated with the former two. But it actually draws me to something profoundly within me, something so basic that it is for many of us one of our first expressions. It may be the beauty of a sunset; it could also be the power of a waterfall, the magic of snow or the excitement of an approaching storm. These chime with our primeval instincts.

For all its edification, education has the disadvantage of silencing this set of reactions. They are ridiculed because they do not talk to the higher mind. As I develop my childish fascination in to an individual art of landscape photography, I build up my critical faculties. After a period, the beautiful sunset becomes yet another sunset, or the wrong kind of sunset. I invent reasons for not capturing the scene. I think it won't captivate my future self, or my peers, or that it won't be worthy of Art.

Intellectual concerns channel my thinking. While my power of thought may remain just as vigorous, it is constricted and guided. This pushes me to explore the ramifications of a narrow concept and build in-depth knowledge. The accretion of information on to such a small area lends gravitas to the work of art, for which the specialist public will commend the artist. The generalist public however will see the greater density of the rendition as a barrier to their understanding. The discussion now encounters a moral question over whether the purpose of the artist is to satisfy specialists, himself included, or make it easy for laymen. The choice of elitism versus demagogy is recurrent but a personal one which we should all answer separately.

Intellectual concerns channel my thinking. While my power of thought may remain just as vigorous, it is constricted and guided. This pushes me to explore the ramifications of a narrow concept and build in-depth knowledge. The accretion of information on to such a small area lends gravitas to the work of art, for which the specialist public will commend the artist. The generalist public however will see the greater density of the rendition as a barrier to their understanding. The discussion now encounters a moral question over whether the purpose of the artist is to satisfy specialists, himself included, or make it easy for laymen. The choice of elitism versus demagogy is recurrent but a personal one which we should all answer separately.

Yet there are many good reasons for indulging my simple urges, foremost of which is that the original reasons why I loved the landscape can speak plainly for themselves. Much is made of how true to the scene photographs need to be: lifelike colours, a little gardening but no digital fakery are essential to the traditional, almost purist approach but not to the more progressive artists keen to let their imaginations run. Should we also debate whether the picture represents the artist's feelings rather than his education?

Without the imposition of guidelines, my art's evolution would be chaotic. With a modicum of control, my understanding grows in strength while my art returns regularly to haunting themes in order to re-appraise them. Then I can build in-depth knowledge of concepts and techniques in several areas, which in turn can cross-pollinate. It also allows for the subject of my fascination to alter and feed off the process of exploration.

I recently visited Wales with the camera gear in tow. I stopped off at Marloes Sands which I had never visited before. The tide was in and the wind was howling a gale but on the plus side, the sky was full of fluffy clouds and the evening sun was lighting them up wonderfully. For all my looking around and pondering, I failed to find a composition which could not be ruined by one criticism or another. I came away without a shot. A couple days later, I was now in mid-Wales, at Nant yr Arian. I had swapped seaside for moorland, my large format camera for a hand-held digital SLR, evening for middle of the day, and importantly a critical mind for an open mind, without fear of the results’ interpretations.

I recently visited Wales with the camera gear in tow. I stopped off at Marloes Sands which I had never visited before. The tide was in and the wind was howling a gale but on the plus side, the sky was full of fluffy clouds and the evening sun was lighting them up wonderfully. For all my looking around and pondering, I failed to find a composition which could not be ruined by one criticism or another. I came away without a shot. A couple days later, I was now in mid-Wales, at Nant yr Arian. I had swapped seaside for moorland, my large format camera for a hand-held digital SLR, evening for middle of the day, and importantly a critical mind for an open mind, without fear of the results’ interpretations.

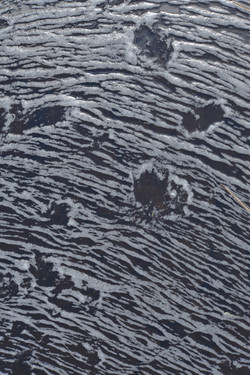

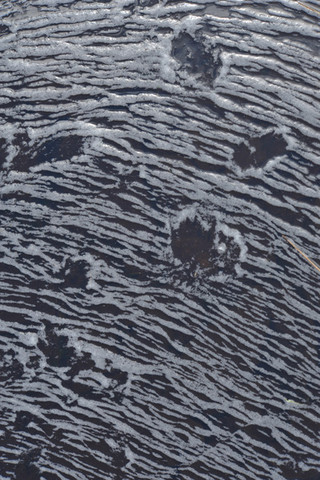

The changes brought about the pictures which illustrate this article. On the surface, they're about mother Nature. I am fascinated by Her diversity of forms, by the interplay of species, and generally by the many things which led me to a career in the life sciences. They also play with a concept which has fascinated the child and then the artist in me: colour. In what can seem a throw-back to Delaunay’s use of work on the simultaneous contrast of colours, I like to juxtapose strong colours.

The photographer in me has taken this further to a general love of contrast. As my art grew, I realised that one of the defining features of a successful picture (by my terms) was the ability to distinguish the visual elements within that picture. So I would use a subject’s colour (hue, brightness, saturation), as well as its textures (including sharpness) and forms. I also learnt to contrast meaning while perversely not varying the visual elements. By themselves, the photographs stemming from this investigation are mostly heavy going and not obvious out of the context of my thinking. Some however provided exciting results which have been used again in this series.

This fruitful walk in Wales has spurred me on to look again at what the landscape can deliver and not to get too hung up on the validity of the work within a narrow context. It’s important not to lose sight of what was fascinating initially. As long as I am enjoying myself, I am probably doing just that.

You can see more of Charles Twist's images at his websites www.chtwist.com and www.citiesandparks.com.